|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Wing Commander RN Bateson 39054 DFC RAF In 1909, Edward VII had ruled Britain and the British Empire for eight years. Though nearing the end of his own reign aged 68, the Edwardian era named for him continued to flourish even as currents of change stirred in British politics and society. In late July, the Daily Mail prize of 1,000 pounds for the first powered, heavier-than-air flight across the English Channel was won by Louis Bleriot of France, landing at Dover from Calais in a monoplane of his own design. Born in the Brighton area in 1879, George Roland (or Rowland) Bateson reached his 30th year in 1909. That Edwardian Autumn, he wed Florence Maud Allen, their marriage registered in the District of Brighton, Sussex. The birth of the couple’s first son, John Allen Bateson, was registered at Portsmouth in December 1910. Their second son, Robert Norman Bateson, was born on 10 June 1912 in the Barcombe and Chailey area, not far from Lewes in Sussex, eight miles North East of Brighton. Young Robert attended school in Hove and later, at Watford Grammar School.

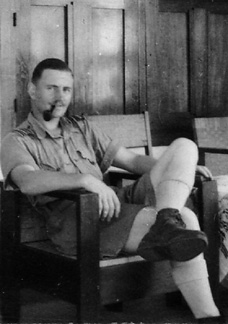

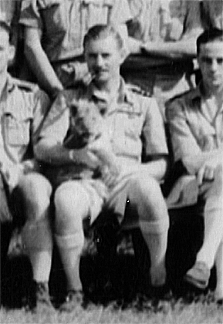

Characteristically photographed with pipe, faint grin, and steady gaze. Cropped from the shot with Adjutant F/Lt JW Bright in Fred Joerin’s Log Book, taken about January 1942 possibly at Helwan. To wear the blue As the RAF grew apace, balancing the complexities of training manpower, stations, courses, and suitable aircraft in quantity saw the elementary stage of Service flying training taken on by the few existing civilian schools. So in mid-July 1936, Pupil Pilot Robert Norman Bateson began his training with Brough Civil Flying School (otherwise No 4 Elementary and Reserve Flying Training School) at Brough, beside the River Humber in the East Riding of Yorkshire. At that date, Brough Aerodrome was the head office of Blackburn Aircraft Ltd, landplane and seaplane makers, who operated the School with a number of their Blackburn B-2 trainers. For its day, the B-2 was a quite advanced single-engine biplane, with its metal-clad semi-monocoque fuselage, leading-edge slats, and side-by-side seating for pupil and instructor. For ab initio trainee pilots then “...the course for the regular personnel at civil elementary schools lasted normally for eight weeks (10 in Winter) during which a minimum of 25 hours dual and 25 hours solo flying was carried out. At this stage, the pupils were civilians although paid by the Air Ministry” At Brough, with F/Lt Stockbridge as his flying instructor, Bateson flew often from 15 July, usually several times a day. Ten days later, Stockbridge was satisfied with his pupil’s progress: early on the morning of 25 July 1936, with 8:45hrs dual in the Flying Log Book, Bateson took his first solo in B-2 G-ACBJ. As Summer passed, the flying hours piled up, at first with Stockbridge still in the right-hand seat, then increasingly with “Self” as sole pilot. Robert Bateson completed his initial flying training in early September 1936, all of it flying the pretty if sedate B-2s. On 5 September, with his Log Book flying summary showing 26:35hrs dual (5:50hrs on instruments) plus 28:10hrs solo flown in just seven weeks, the Brough civilian CFI signed him out with the admirable if customarily brief assessment of proficiency: “Above Average”. For King and Country Bateson’s Short Service Commission as Acting Pilot Officer was recorded in the London Gazette of 22 September 1936, with effect from 7 September 1936. From 19 September, he was posted to No 2 Flying Training School at RAF Digby in Lincolnshire, 12 miles South of Lincoln and just three miles from the LNER station in the nearby village. Four days later, he was back in the air, this time in a rather livelier beast than the B-2s of Brough. Perhaps it was a quietly relished Digby joke when new boys drew, as their flying instructor, Sergeant Pilot Hart. However it was, Acting Pilot Officer pupil and Sergeant Instructor set off together that Summer afternoon for a short Digby local—in Hawker Hart (Trainer) K6459. Serving the RAF as a two-seat day bomber in quantity from 1930, for its day the Hart was sufficiently spirited that by 1932, older and slower AW Atlas trainers were being replaced. To better prepare trainee day-bomber pilots soon to join operational Hart and Hind Squadrons, Hart Trainers had been put into production. With armament deleted, engine de-rated, full-dual control to the instructor’s rear cockpit, and a re-jig of upper-wing sweep, large numbers of the more suitable Hart (T) were produced as expansion of the bomber force gathered pace, for service as advanced trainers in RAF FTS units (and on bomber Squadrons too, as they started re-equipping with Hinds). After seven flights amounting to 3:40hrs in a week, by 1 October 1936 his aptly named instructor had seen enough for Bateson to take his test with their ‘C’ Flight commander, F/Lt Lewis. All was well and within minutes, Bateson was off again, solo in Hart (T) K6440 with 58:45hrs in the Log Book. By the end of the month, his total flying time had reached 68:10hrs, 34:50 of it solo. In the School’s Hart Trainers and Audaxes that month, he flew for 10:05hrs, 6:40hrs of it solo. Meanwhile, older brother John, having started training around six months earlier than Robert, had been commissioned in early April 1936. In October, Acting P/O JA Bateson was among those selected for the School of Air Navigation at Manston in Kent, the latest development in the RAF’s slowly awakening awareness of the need for better navigation skills generally (and for qualified full-time navigators too). Confirmed as Pilot Officer in February 1937, at the end of March John Bateson was posted to 217 (General Reconnaissance) Squadron, an Avro Anson unit at Boscombe Down. There, long over-water anti-submarine patrols called on the navigation skills of pilots and navigators alike. Promoted to Flying Officer, JA Bateson was still with the Squadron at Tangmere in January 1939, patrolling the English Channel and beyond in their “Faithful Annies”. On entry to service in 1936, the Anson was not only the first of the expansion scheme era RAF monoplanes but also the first with retractable undercarriage—at once a novelty and a curse. It was retracted by hand-crank: “approximately 160 turns” advised the Pilot’s Notes coolly (Air Publication 1525A—PN, para 7). Later, Ansons were to train many pilots in twin-engine flying, and many more navigators and wireless operators in its comparatively spacious cabin. The last Ansons were withdrawn from RAF service as late as 1968. For Bob Bateson, November 1936 passed with more hours flying the Hart Trainers and occasional Audaxes, in more demanding flying and longer cross-country exercises, mostly solo. By the end of the month, solo flying had risen to 45:25hrs, the total to 83:45hrs . In the first month of Winter, flying time fell off a little, amounting to 6hrs in all but with the end in sight. One way and another, for Britain it was a Winter of some discontent: the uncrowned Edward VIII abdicated on 10 December. However, for Bateson a final hour on instruments with Sergeant Hart on New Year’s Day 1937 was followed with the hard-earned stamp: “Qualified for Flying Badge”, dated 2 January 1937. His Pilot’s Wings would shortly be issued and sewn on the tunic. Moving to ‘B’ Flight of the Advanced Training Squadron at 2 FTS with nearly 92hrs in the Log Book, there came a break of four weeks with no flying at all: whether it was leave or a hard winter in Lincolnshire, a break just long enough to give a new pilot pause for thought. On 3 February he was back in the air, first taking a short local solo in the morning, and after lunch an equally brief formation stint, again solo (and both in Audaxes). Enough to feel current again, but it was another six days before more serious flying came his way: an 85 minute cross-country, solo in Audax K7351. All well, the rate of flying and level of responsibility now increased, either taking turns as Pilot and Observer with other Acting Pilot Officers on navigation exercises, or on reconnaissance and instrument flying with senior pilots. The late Winter of 1936/1937 was in fact quite hard. February 1937 was notably wet across much of England, turning late in the month to very heavy and wide-spread snow falls in the North later extending Southwards. It was late March before the weather began to improve. That might perhaps explain another longish break in flying for Bob Bateson from 22 Feb to 23 March. Still, by the end of that month in ‘B’ Flight, his total flying time had passed the 100hrs mark. Come early Spring, and the pace picked up markedly. Occasionally with F/Lt Sloan at the stick, but more often “self”, and often enough with A/P/O Dugdale as Observer, he flew almost daily, and sometimes two or three exercises a day. Near the end of the month, advanced flying reached the serious stage: taking turns with Dugdale, they spent two long mornings flying Audaxes up to 10,000ft and off to the range. “Bombing”, recorded the Remarks column, phlegmatically. By April’s end, the Log Book showed 124:20hrs in the air, 70:45 of it solo, 43:25hrs of that in the Audaxes and Harts of 2 FTS. During the first two weeks of May the flying was a touch less busy, but again he and Dugdale took turn-about to go a-bombing. From 11 May, there was a two-week break from flying. In London on 12 May, His Majesty King George VI was crowned at Westminster Abbey. Then, on the 21st of the month, with 130:50hrs flying logged, Bateson’s time at Digby was done. The CO, S/Ldr HE Power, signed him out with the hard-earned RAF assessment of proficiency as a pilot: “Average”. He had flown the Audaxes and Hinds solo for 48:05hrs, gone bombing on the range as Pilot or Observer four times, and recorded satisfactory results in ground gunnery, air firing, camera gun and bombing. By the standards of those far-off days, A/P/O RN Bateson was ready to serve his newly-crowned King and his country on an operational Squadron. “Officer to report on joining...” Four days later, he was in the air with CO S/Ldr DH Carey, to make acquaintance with the Hind in a short late afternoon local: with all well, an hour alone followed immediately in the same aircraft, K5522. Taken on 103 Squadron charge with their re-forming at Andover in August 1936, in later service K5522 survived a rich assortment of adventures until July 1941 at 1 FTS, when the engine cut on approach, ending in a stall and crash at Netheravon. By coincidence, another ex-103 Squadron Hind, K5520, later made it’s way to 211 Squadron when they deployed to the Middle East in 1938. In the way of the Service, Bateson was now about to have his first encounter with the mysteries of RAF manning and posting. On 2 June, less than two weeks after arriving at Usworth, Bateson left 103 Squadron, posted to 113 Squadron at Upper Heyford, 250 miles to the South in Oxfordshire. No 113 (Bomber) Squadron had only re-formed as a Hind bomber unit on 18 May—just three days before his arrival at Usworth. With RAF expansion accelerating, the early stages of such re-establishments could be pretty testing, as 211 Squadron would also find in the first weeks of June. In Bateson’s case, looking at the dates and the Squadron numbers, it’s possible the reason for his move was quite prosaic: perhaps a simple typing mistake in the order or its signal had sent him North to join well-established 103 Squadron, when all along the intent was to send him to 113 Squadron as it stood up. In any event, on 4 June he reported for duty with 113 Squadron. 113 Squadron Before lunch on 8 June, it was time to have a look around the new patch, with a 30 minute local alone in Hind K6806: a new machine, of the third production batch, it had been on Squadron charge less than three weeks. After lunch on 10 June, a little variety came Bateson’s way. Upper Heyford was also home to the equally newly established 233 Squadron, equipped with nice new Avro Ansons. That afternoon, with P/O Downton at the stick, they set off to Manston via Henlow in Anson K8777, to collect parachutes.

Three Hinds of the Squadron en echelon, somewhere over the UK, at some date between May 1937 and March 1938. The further aircraft is K6806, which Bateson flew quite often from June 1937 through to February 1938. It’s presence helps date the image, as it passed from 113 Squadron charge in April 1938, before they left for the Middle East. The nearer machine, K6802, was flown by Bateson occasionally in the UK and the Middle East. Flown by the then CO S/Ldr Cator on 23 December 1938, it stalled on landing at Heliopolis, collapsing the undercarriage and nosing over, damaging the propeller. Thereafter, the tempo on 113 Squadron was brisk as they worked up under Batholomew’s command. Bateson now flew most days in the Hinds, and often for two, three or four times a day, on local reccos, formation practice and cross-countries aplenty, with Aircraftmen and Sergeant aircrew of the Squadron in the back seat. Formation Leader, Press Photography (Formation), Observer Test, and Instruction on New Type: now Acting Pilot Officer Bateson was showing more junior aircrew the ropes. Heady stuff, less than a year into his RAF service. In June 1937, he flew for 22:40hrs, bringing solo time to 99hrs of his 157:00hrs total—and completing his his first Flying Log Book. Through July, the workload stayed pretty brisk with 25 flights, often morning and afternoon, usually now with AC Lee in the rear cockpit. Most flights were formation practice of one sort or another, often as cross-country exercises, and quite often as formation leader. On 19 July, he and Lee had what looks to have been an exhilarating day, starting late in the morning with two terminal velocity dives from 11,000ft, the first reaching 312mph indicated. After lunch, up again, leading a cross-country formation over to Manston. There, quite late in the day, they were up once more to carry out the set-piece: Raid No 1. Quite a day. The next day, they returned to Upper Heyford via Hornchurch. The month ended with 118:10hrs as pilot in the Log. The late Summer was markedy less busy, as the Squadron prepared to move North to Grantham in Lincolnshire at the end of August. Including visits to their new Station, Bateson’s flying for August was just 5:20hrs. Meanwhile, at Mildenhall, 211 Squadron were also preparing to move. The two Squadrons were to be based at Grantham until they both left for the Middle East in the Spring of 1938. At Grantham, 113 Squadron was soon back in the swing of things, the flying tempo brisker still throughout August and September. Usually with Lee in the Gunner’s cockpit, Bateson carried on with the round of formation and navigation exercises, with radio or gunnery exercises for variety, plus occasional weather tests. Early September brought gazettal confirming him as a Pilot Officer, with effect from 13 July. By mid October, they were practising flare-path landings: it was some time since he had done any instrument flying. By the end of October, another 64 flights were entered in the Log. In November, the late Autumn weather was less encouraging and the workload eased, with just 17 flights. The shorter days brought another change: two night flying exercises. In the manner of the time, on a day bomber Squadron, it was quite some time since he had even flown on instruments. With the year drawing to a wintry close, flying activity fell off: just 10 flights for December. Still, the weather must have been reasonable enough on 14 December, as that day he took to the air in single-seater Gloster Gauntlet K7859 for 50 minutes of local flying, aerobatics and in formation to Digby, where the task next day was a Hind operational exercise: a bombing raid. As 1937 ended, P/O Bateson had been busy for six months on an operational Squadron, with plenty of flying, whether formation leading, training, or a variety of navigation and bombing exercises. The grand totals in the Log Book now showed 235:50hrs flying, 189:50hrs as pilot (with 12:30hrs on instruments and 3:20hrs at night). At the end of December, it was time for a new CO. Bartholomew left them, slated for the RAF Staff College and an Air Staff job. Post-war, at the end of his time as Air Attaché to Turkey, Air Cdr Gilbert Bartholomew was among the senior RAF officers who died in a civil flying accident at Ankara in August 1949). In the New Year, S/Ldr FG Cator 16072 took command. He was to lead them for over a year, from Home service to Egypt. An RAF Cranwell cadet commissioned in 1922, Cator had prior experience of the Middle East from a 1930 posting. Twice mentioned in despatches and a Group Captain, he survived the war to retire in 1951 with the award of a CBE to his credit. The Squadron will proceed... Unremarked in his Log Book, from early January until the end of March P/O RN Bateson was ‘B’ Flight commander. February was just as busy, 19 flights amounting to 17:50hrs—seven of them bombing exercises of one sort or another, with a couple of instrument flying sessions to boot. In mid-March, the Squadron was informed that it was to proceed overseas. Up to the middle of the month, Hind flying continued at a steady rate as in February but with more marked offensive intent, plus some more night and instrument time. After this time, AC Lee appeared no more as Gunner on Bateson’s flights. Preparations for the overseas move then took precedence, with aircraft being ferried to RAF Sealand for dismantling and crating. Bateson’s own flying for March ended in the third week of the month with a two day return trip to Sealand via Ternhill in Magister L5950, apparently to collect his occasional flying crewmate P/O Willis who came back with him in the rear cockpit. The Log Book now showed 282 flying hours, 236:00 hrs of that solo, with 19:05hrs on instruments or at night. The Squadron strength was now made up from two to three Flights, 18 Hinds in all, but on a non-mobile basis. Among those posted in at the beginning of April was one F/O Gordon-Finlayson. For his final flight in the UK for five years, Bob Bateson now managed to arrange some useful experience off-Squadron, with a special bonus. On 4 April 1938, he undertook a night cross-country and bombing exercise for 2:30hrs as 2nd pilot or passenger in an Avro Anson—piloted by his brother John of 217 Squadron at Tangmere. After returning from four weeks embarkation leave, all hands were ready for the move on 30 April . On that day, the men of 113 Squadron left Grantham by train and embarked for the Middle East at Southampton, aboard the long-serving HMT Lancashire. Travelling with them were the men of 80 Squadron and 211 Squadron, their crated aircraft transported aboard a cargo vessel for the Packing Depot, Aboukir. City of the Sun The 216 CO S/Ldr WN Blain offered the newcomers one sort of practical welcome as they awaited re-erection of their aircraft. On 12 May, he took Bateson and nine others aloft in Valentia KR2792 (a rebuilt Victoria V) for a 50 minute tour around Helio and environs. From the aerodrome on the North East outskirts of Cairo, the Pyramids at Giza were about 15 miles away across the City and the Nile, in easy reach for the doughty transport, droning about at 120mph. While 113 Squadron continued to sort out its equipment and aircraft, on 20 May Bateson was able to get some air time after a break of well over six weeks. Thanks this time to 208 Squadron, he took a 30 minute flight around the local area in Audax K3115. Later serving with 4 FTS, at the siege of Habbaniya in 1941 the aircraft is said to have been laid out as one of the “Hurricane” decoys. At the start of June it was time for P/O Bateson’s annual assessment. His Service flying stood at a tick under 300hrs in total, 160:10hrs of that flown as pilot in the 12 months since June 1937. While gunnery, bombing and navigation all drew the usual conservative “Average” rating, in a nice compliment, Cator judged his ability as a light bomber pilot as “Above average”. In the hard-marking RAF that was certainly recognition. By 8 June, some of their own aircraft were ready and Bateson took Hind K5556 up alone for a quick circuit to shake off the cobwebs. The following day, the Squadron stood down for the King’s Birthday holiday. On 10 June he took K5556 alone, again, for a longer “local”. Thereafter, the Squadron resumed a busy flying schedule. In June, 21 flights for Bateson, 18 of them in Hinds on formation and bombing exercises, and for variety, a day long stooge of 5:30hrs out to Ramallah and Port Said and back, getting the lie of the land as passenger with P/O Tomlinson of 216 Squadron at the controls of Vickers Valentia K3604 ’W’. Throughout July, August and September 1938 the Squadron kept the tempo high, while European tension was driven ever higher by the German Chancellor. Between the bombing, formation and navigation exercises, aerial photography and night flying were undertaken more often, and twice there were flights out to Mersa Matruh, 260 miles West on the Desert coast, 2 hours or more away in a Hind. In the three months from July, Bateson undertook 85 flights in the Squadron Hinds, all but three as pilot, to reach 330:50hrs flying as pilot, 16:20hrs of that at night. From 3 August, he was Acting Flying Officer, moving from ‘B’ Flight. While crewing was yet to become permanent, from then on Cpl Durrant often took the rear seat as Gunner cum Wireless Op. At the end of the month Bateson had the pleasure of signing off his own Log Book as “RN Bateson P/O, OC ‘A’ Flight”. Towards the end of September, a new duty came his way, reflecting the change in status: “Flight Commanders Test (New Pilot)”, undertaken several times for new A/P/O arrivals.

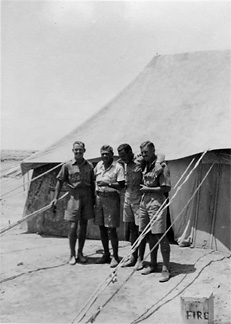

Here the aircraft is running up, the airman acting as ballast covering up against the sandy blast of the Kestrel’s slipstream. The Squadron Leader’s insignia is emblazoned on the fin. No date, but from the dress and airfield hard-standing, plainly a Middle East setting, sometime after May 1938 and very likely Heliopolis. Bateson flew this aircraft on numerous occasions from August 1938 until April 1939. To the Desert At that time, the RAF was expecting that “Italy would be the principal enemy in the Middle East”—an assessment that proved correct once war did break out, remaining so until February 1941. The need for the RAF to take such forward positions against any Italian advance had been realised back in 1936: the Libyan border was 300 miles West of Alexandria. For Hinds in 1938, the best use of their range and limited war-load against any Italian advance would be from bases closer to the action. Mersa Matruh, with its rail access back to the Delta, was less than 150 miles from the Libyan fontier. Meanwhile, in Palestine, 211 Squadron was about to be withdrawn to Helwan and prepare for a move to El Daba as part of the provision for possible war. Both Squadrons learnt a deal about mobility in Desert conditions in a fortnight of flurry. By 11 October, 113 Squadron was back at Heliopolis, where they practiced hard for the great mass fly-past of 18 October: 140 RAF aircraft in formation over Cairo in a show of strength to bolster Anglo-Egyptian relations. Bateson, in Hind K5420 with LAC Angell, flew as Leader, No 2 Flight of the Squadron’s 12 aircraft contribution. Not suprisingly, although the crisis passed, the state of readiness of the Squadron remained high, flying activity indeed increasing by December. By then, the emphasis on bombing exercises (high and low level, and dive bombing) was clear, together with more night flying. Formation practice, cross-countries and fighter affiliation all played a part, too, the routine broken only to search for a Blenheim missing over the Sinai from 11 to 14 December, 211 Squadron also taking part. The aircraft was not found. By the end of 1938, after 18 months service with 113 Squadron, F/O Bateson had advanced in rank, to command of a Flight, with his Flying Log Book standing at a grand total of 463:30hrs service flying, 417:30hrs as pilot (26:55hrs at night). Change in the air By 7 February, Cpl Durrant had advanced to Sergeant and was manning the rear seat for Bateson on most flights. Over the course of February, they kept the pace up, flying the varied programme of exercises every day, often several times a day, with plenty of visits to the Western Desert bases, or East to Ismailia and the Suez Canal. At the end of the February 1939, Cator left them, S/Ldr Gerald B Keily 27256 from 216 Squadron taking over command. An experienced Flight Commander, he had also served with 45 Squadron, after several years instructing with 4 FTS at Abu Sueir near Ismailia and the Suez Canal. In March, the programme eased a little, perhaps as result of aircraft maintenance in preparation for a move: Bateson recorded a number of flights as “Engine test after fitting new cylinder blocks”. There was also an amount of survey flight training to and from Mersa Matruh, followed late in the month by reconnaissance of the Desert for more landing ground sites. On 23 March came his Gazettal to Flying Officer, with effect from 13 February. Over the first three months of 1939, Bateson’s flying duties added well over 80 hours to the Log Book, which at the end of March showed a grand total of 550:05 hours service flying, 504:05hrs as pilot, 37:00hrs of that at night. Flying was a little busier in April but rather different in character, with some restrictions ordered by HQ Middle East. No more practice bombing, quite a lot of assorted air tests, some recco work over the Desert coast, and so on. On 7 April, Italian troops invaded Albania, reflecting the long-standing ambitions of Benito Mussolini. In view of the increased tension, on 21 April 113 Squadron moved forward from Heliopolis, “up the Blue” to El Daba for a month. They found 211 Squadron had arrived the day before. At the end of the month, Bateson was able to sign off his Log as F/Lt. The Blenheims arrive Blenheim Delivery Flights from the UK continued throughout 1939 and 1940. In retirement, Bob Bateson recalled "...it was probably in 1939 that they started ferrying Blenheims out from the UK and there's quite an interesting little story associated with that because, when the first Blenheims arrived, they landed at Maaten Bagush which was the airfield I was on at the time. Of course we clustered around straight away to see these new aircraft - absolutely marvellous - monoplanes - twin engines - you name it they'd got it. [They] even had radios in it and navigation equipment and so on. The chap got out of the first aircraft and I met him and made him welcome [and] asked what he wanted - they wanted petrol and some food. He said, "Your name's Bateson." And I said, "How on earth do you know that?" And he said, "We went through the conversion course at Tangmere and the chap running the course said, "If you're met by somebody smoking a pipe it'll be my brother." My brother was running the conversion unit at Tangmere in this country [UK] and sending them out to the Middle East..." [Difficult to date and place this nice yarn exactly, beyond early 1939. The context is pretty clearly before 113 Squadron’s own re-equipment. They had spent some weeks at El Daba and from there or from Helio had often visited Mersa Matruh—from where the Landing Ground at Ma’aten Bagush is only some 25 miles back East along the coast. However, neither Bateson’s Log Book nor the Squadron diary Form 540 (rather sparse for the first six months of 1939) mention any early 1939 activity at Maaten Bagush itself. When the war did finally reach the Middle East on 10 June 1940, it was to be their War Station. Still, there was plenty of flying activity along that 80 mile stretch of Western Desert coast in early 1939. A true story, vividly recalled, of a brother by then long dead: worth the recounting, whether it was Mersa Matruh or Maaten Bagush.] On May Day, the 211s returned to Ismailia, to await re-equipment with the twin-engine, three-seat Bristol Blenheim I in place of their Hinds. Despite the political situation, when an Italian aircraft went missing in early May, 113 Squadron lent a hand, Bateson taking off at first light on the 4th for a long search out to Sollum and Sidi Omar, and again in the afternoon with Sgt Durrant, tracking up the border to Sollum, to return on dusk to Mersa Matruh. That month, there was quite a lot of reconnaissance activity, along with the local flying and air tests. On 21 May, 113 Squadron returned to Heliopolis, it being their turn to convert from Hawker Hind to Blenheim I. The time for Bateson’s annual assessment had come again. Over the 12 months since June 1938, he had flown 329:45hrs, 33:00hrs of that at night, of his grand total as pilot of 566:15hrs. If his CO felt some satisfaction in completing the usual Form 414, it must have been at least matched by Bateson’s own reaction. In all four classes (as Light Bomber pilot, as pilot/navigator, in bombing and in air gunnery) the slip pasted into his Log Book bore the same assessment: “Above average”. Heady stuff, in the hard-marking RAF. On the same day, 1 June, S/Ldr Keily flew the Squadron’s first Blenheim to Helio, from the Depot at Aboukir. His long period of instructing at 4 FTS was also recognised at this time, with award of the Air Force Cross. On 14 and 15 June it was Keily himself who took Bateson up in the dual-equipped Blenheim I L1499, first to observe the CO instructing Sgt Bagguley, then at first light the next day as the pilot under instruction, with P/O Williams along to watch. Shortly after landing, Bateson was off again solo, for an absorbing 35 minutes of circuits and landings in L4824. Meticulous and not quite satisfied, perhaps? Certainly later that morning he was up again, in L1542, for a further set of circuits and bumps. If getting obsolescent for Home Squadron use in the last Summer of peace, for those days in the Middle East, the Mark I Blenheim was quite modern, quite fast and quite powerful. Mishandled, the aircraft could certainly bite, especially if the two Mercuries were subjected to hamfisted treatment on take-off—or attempting a hasty go-round. So at first light on 16 May, he was up again, by now confident enough in L1542 to spend time getting the feel of single-engine flying (a potentially difficult prospect, especially on take-off or landing). The next four days literally flew by, as several times a day he took groups of personnel up in assorted Blenheims for air experience, or out to the Aircraft Depot at Aboukir (only 45 minutes away in a Mark I) to collect new aircraft, or to acceptance test the new arrivals. And to practice single-engine flying again, solo. After a short break, it was time for serious work. The Squadron’s new flying programme began in earnest, with four days of navigation, bombing exercises, and air gunnery. After that first 40 minutes dual, by the end of June 1939 F/Lt Bateson had added a tick under 12 hours as a Blenheim pilot to his Log in 14 days. The Squadron as a whole flew 225hrs over the month: a respectable total in the midst of conversion. In July the Squadron started to pick up the pace, flying 230hrs. For Bateson, flying duties were well up with 20:25hrs in the Blenheims, much of that on bombing exercises by day and night, and a fair amount of formation practice: in the bigger Blenheim, with a single-gunned turret, good formation flying was essential for effective defence. By August, 113 Squadron were confident with their new aircraft. That month the Squadron flew 293hrs. Not only did the flying pace pick up markedly: their state of readiness was such that from mid-month, at weekly intervals, they were able to spare three crews (Sgt Bagguley & co, then Sgt Marpole & co, and finally Sgt Racliffe & co on 27 August) for Home and Blenheim Delivery Flight ferry duties back to the Middle East. Like Burnett and Wright of 211 Squadron, for Marpole at least it was January 1940 before he was able to return to Egypt, his return overtaken by the outbreak of war in Europe. For Bateson, on top of the usual bombing and formation exercises, he was able to fit in a number of air and engine tests (having forced-landed L1542 in the dawn at Aboukir after the port engine failed on an operational flight on 16 August) and a number of Blenheim instructional flights for P/O Lands as well. In all, he flew 27:20hrs in Blenheim that month. His service flying then stood at 688:25hrs. Meanwhile in Europe, Germany and Russia had reached a fateful accommodation. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of mutual non-aggression, signed on 23 August, boded ill for Poland. War was now certain to come—and soon. Phoney War In Egypt, 211 Squadron had already moved to their War Station at El Daba. At Heliopolis, 113 Squadron spent six days firstly at six hours, then two hours, and finally four hours notice for active service operations, during which time general mobilization of British forces in Egypt was ordered on 4 September. Still, war did not come immediately to the Middle East, Il Duce content for the moment to remain a “bellicose non-belligerent”: to strut, in other words, rather than to strike. In truth, whatever destruction his forces had been able to wreak upon the rural peoples of Libya, Abyssinia and Albania, no element of the Italian armed forces was ready to prosecute war against a well-armed modern opponent. The Poles, under swift attack by German and then by Russian forces, were overwhelmed. Surrender came after less than five weeks of blitzkrieg. The uncertain period that followed soon came to be known as the Phoney War, though for Poland nothing could have been more genuine. From the point of view of Britain, the Commonwealth, and France, at least some months still remained in which to prepare for direct hostilities. On 7 September, 113 Squadron resumed normal working hours at its permanent station, Heliopolis. Resuming live bombing practice, by the end of the month the Squadron had flown 289 hours. Bateson as ‘A’ Flight commander had contributed 22:00hrs of the total in 21 flights, evenly divided between dual instruction (with solo checks) and live bombing on the Suez Rd ranges (in various evolutions of Squadron formation). October passed at a similar pace: 295 hours flown by the Squadron. Under orders to revert to practice bombs on the ranges, the flying duties were a mix of high and low level bombing, cross-country navigation, and tactical reconnaissance exercises, plus rather more night flying. Bateson himself undertook about the same amount of flights, adding 19:55hrs to the Log Book, often with Sgt Horton as Observer and any of a number of Gunners in the turret. Through November the Squadron exercised just as hard, 311 hours flown, much of it over the bombing ranges (several times at night) and on gunnery exercises. For Bateson, flying duties were a touch lighter at 17 flights in 17:20hrs flying. For the last month of the year, the flying hours did relax a little, although exercises reached a climax mid-month. The Squadron sent nine aircraft to Fuka, from where over the two days 12 and 13 December they mounted exhilarating (if tiring) long-range Air Defence mock attacks on targets at Alexandria and Cairo, carrying full war loads. Of these, Bateson took part in the low level op against Cairo Main Station flying at 300ft (sic!), and the next day at 18,000ft on oxygen against Alexandria. As his Squadron stood down for the 1939 Christmas break, Bateson had flown 15:00hrs, 3:00hrs at night, for the month. His Service Flying now stood at 762:40hrs, 133:55hrs of it in the Blenheim Is of 113 Squadron. On 27 December, S/Ldr Keily returned to the UK for Blenheim Delivery Flight duties. “Velox et vindex” For 113 Squadron, welcome changes came in March 1940, with the return of their CO, S/Ldr Keily and leading a flight of Mark IV Blenheims no less. Then on 20 March, the AOCinC visited Heliopolis to present the Squadron with their RAF badge, the crosses and swords recalling their World War I service in Palestine: “swift to vengeance”. Flying activity was reduced in the last week of March as they carried out a practice pack-up, ready to move to a War Station if need be. In the three months to the end of March, Bateson himself was busy with Mark I training and test duties, once or twice put off by the odd sandstorm or low cloud. There was plenty of variety: line-overlap photography (for mapping); bombing exercises high and low level; navigation and cross-country flights including a visit to Habbaniyah, Amman and Lydda; formation, cloud, and night flying; gunnery; some dual instruction duties; engine and rigging tests; and on one occasion, a demonstration flight to show how to get out of strife with a cutting engine at take-off. Many of these flights were in L1542, a Mark I which later went to 211 Squadron. With another 50:45hrs on Blenheim Is, his service flying total stood at 811:50hrs. As the Squadron started receiving their Mark IV machines, the Mark Is were gradually being moved on, with BDF ferry duties to other stations. It was September before the last had gone. In April they were exercising with their own Mark IVs, and in May, taking some on BDFs down to Aden. By then it was Spring in Europe—the poppies were blooming again in Flanders. On 9 April, the Wehrmacht had invaded Norway and Denmark. The poor Danes, overwhelmed, surrendered that same morning. On 10 May, blitzkrieg spread West, with attacks against Holland, Belgium and France. In England, Churchill succeeded Chamberlain that day. The Phoney war was over. In Egypt, there was still time to exercise. For 113 Squadron, working up with the Mark IVs was the big task. On 3 April, Keily took Bateson aloft for 2 circuits in Mark IV L9218, and that more or less set the pattern. Lots of flights, often short, as the gen was passed on to aircrew of the Squadron: take-offs, landings, stall tests and the like, interspersed with several long-range flights to check the endurance of the new model, ranging as far as Jaffa and Port Sudan at 14,500lb with full war load. Bateson accumulated 20:15hrs in the Mark IVs in April. May was busier still, as the war in France grew ever grimmer. That month, of the Squadron’s total of 360 hours, F/Lt Bateson flew 34:10hrs in all, 22:45 of that in the Mark Is still on charge. There at the end of May, their Operations Record Book came to a temporary end. An undated page, handwritten, punctuates the record: “JUNE—AUGUST 1940 War comes to the desert ITALY DECLARED WAR ON FRANCE & GT BRITAIN That afternoon he took off for Maaten Bagush in Mark I L8463 with P/O Shekleton and Sgt Gilbert as crew, and LAC Thomson as passenger. “On move to Sqdn War Station” he noted. Over the next 11 days, he flew six operational sorties against the Italians in Libya. For some reason, Keily and Bateson flew a party of 17 back to Heliopolis and on to Ismailia on 26 June, in Valentia JR9765—a move unremarked in the Middle East Campaigns narrative. Through June and July, 113 Squadron was very active on raids and reconnaissance sorties over Libya, losing four aircraft on operations in June with six men killed in action and six taken prisoner by the Italians. By 3 July, Bateson was back at Maaten Bagush, mounting a long photo recco sortie, dashing back to Ismailia with the film that evening, and on to Heliopolis next morning with the prints. By the end of July, he had undertaken two more such sorties. On the second, a fuel feed problem caused him to forced land at Sidi Barrani after 5 hours in the air: “Two dead motors” he noted, laconically. No harm done and by the end of the month, he had clocked up 12 ops, including the three deep reccos, mostly with Shekleton and Thomson as Observer and WOp/AG. The Squadron took no casualties that month. Early August was comparatively relaxed, with 48 hours leave for the three at Helwan. Like 211 Squadron, war-time or not, they took L8446 (a Mark I) as their leave “bus”. On 9 August they headed back to Maaten Bagush in the early morning. By late morning, they were back in the air, off to Benghazi on a 6:20hr photo recco, flying 1,200 miles at 20,000ft. Early the next morning, off to Helio with the results: “AOCinC Very Pleased”, Bateson noted—and flew back to Maaten Bagush late that afternoon. Four flights in two days, 10:50hrs in the air. By the end of the month, the ops tally was 17 for Bateson, including four more of the long range reconnaissance flights in Mark IVs (of which the last two were of 7 hours or more duration). His last raid in a Mark I came on 31 August. There was cause for some celebration for the Squadron when on 20 August the award of a DFC to the CO, now S/Ldr Keily DFC AFC, was gazetted. The month ended with nil casualties in action. It was 13 September 1940 before Italian ground forces finally advanced into Egypt. Having taken Sidi Barrani and the local Landing Grounds, by 20 September they were already digging in. The Italian advance had run out of steam, one week and 60-odd miles into Egypt. That month, Bateson was very busy, adding 35 flights to the Log Book. While bringing the ops tally to 27, including another 6 hour recco flight out over Northern Libya and Benghazi, he was also able to fit in a number of dual instruction and supervision flights on the Mark IVs. On 12 September he made two last flights in a Squadron Mark I, taking L1542 with 4 passengers to Sidi Barrani to salvage a forced-landed Blenheim. On top of all that, there were satellite ‘dromes to check, at “Waterloo” (LG 68) and at Zimla (both lay near the road, between Bagush and Fuka). By the end of the month he had flown well over 50 hours all up, in Mark Is and Mark IVs, the service flying total standing at 1027:30hrs. The Squadron was again suffering casualties, by accident and in action, the CO among them. On 18 September, nine aircraft attacked El Tmimi against ineffective pom-pom fire and severe CR42 opposition. In Mark IV T2048, S/Ldr Keily and his crew P/O JS Cleaver (Observer) and Sgt J Jobson (WOp/AG) were shot down in flames. Keily survived and was taken PoW. His crew died. Bateson assumed temporary command of his Squadron the next day and Acting Squadron Leader rank shortly after. Keily, born in India in 1904, had joined the RAF in 1929. He was a very experienced pilot by the time he came to command the 113s in early 1939. Gazetted Wing Commander on 1 September 1940, he ended up in Stalag Luft III and survived the war. Made Group Captain in 1947, and acting Air Commodore in 1949, he was seconded to the Pakistani Air Force for a time. Substantive Air rank came in January 1952. Gerald Barnard Keily DFC AFC retired from the RAF later that year and died on 14 September 1962 in Wales. October began with a Squadron raid from Zimla on Bengahzi, the nine aircraft slathering the port area with SBC loads from 15,000ft to no opposition. Most of the action that month was from Zimla, and much of it at night with five raids all on Benghazi, all of them from inland via Siwa Oasis. By the end of October, Bateson’s ops tally stood at 34, and his flying for the month 55:45hrs, 19:20hrs of that on the five night raids. Across the Mediterranean, Mussolini’s forces entered Greece across the Northern border with Albania on 28 October. Although there was no Italian advance in the Desert, for 113 Squadron the operational tempo remained pretty brisk over the Winter months of 1940, mainly daylight raids from Zimla in November. In December,, the initiative passed from the Italians with British Commonwealth forces moving forward. By 9 December, the Italians were falling back from Sidi Barrani. There was quite a bit more night action for 113 Squadron, increasingly from Waterloo, in support of the ground offensive. As CO, Bateson was still finding time to find and test out new Landing Ground sites, but markedly less time instructing. By the end of the year, after nearly seven months of shooting war, he had completed 230 hours operational flying, in 54 raids and recco sorties, for a service flying total of 1182:30hrs. Since hostilities opened in the Desert, his Squadron had lost 10 aircraft on operations, with seven men PoW, 19 killed and one injured. One pilot died in the course of night flying. 1941 By 31 January, in almost eight months on operations, he had carried out 66 raids and reccos in 263:40hrs of operational flying, mostly in Mark IV Blenheims. Then, with the fortune of war for the moment in their favour, it was time for Bob Bateson to leave his Crusaders. The tides of conflict were to ebb and flow across the desert until well into 1943, but Bateson’s duty now lay elsewhere. The Log Book tells the story 1400 30/1 [Blenheim IV] T2182 Self, Mohammed Hassan Khalil, F/O Mann. Command of 113 Squadron now passed to W/Cdr RH Spencer. The Squadron carried on desert operations for some weeks, before being sent to Greece in March. In that doomed campaign they too were badly knocked about, all their remaining aircraft destroyed on the ground at Niamata in April. By the end of May they were back in the desert, on ops at Maaten Bagush once more. Awarded the DFC in July, by August Spencer was gone, killed in action on 31 August. There we must leave the 113s, fighting hard “up the blue”: at the end of December they were to be the first of the four Middle East Blenheim Squadrons to head East to take on the Japanese. Back in Cairo on the Air Staff at HQ RAF Middle East, Bateson got to grips with staff work. Not a man to sit back with feet up on the desk for long, Bateson found plenty of opportunity to stay current in the air, flying to and fro by Hind, Magister and Proctor in the course of duty. Often enough as pilot he took more senior brass as passenger, as they looked into aspects of twin-engine training. The Martin Maryland was starting to replace the Blenheim about then—indeed, for a time, it had been mooted that 72 OTU be Maryland equipped. On Anzac Day 1941, a change of focus came his way, with a stint at 202 Group HQ Heliopolis, apparently while looking into Ops Training. For a time at Helio, he was able to take up instructing again, a decorated Air Staff Squadron Leader showing Sergeant pilots how to encourage a Blenheim to do its best. After the early elation of recapturing Sidi Barrani and Tobruk, in February 1941 the arrival of Rommel and the Afrika Korps in Libya brought a fresh round of fighting withdrawal, back to the Egyptian border by May 1941. A dark period of the war, with defeat in Greece, the great strain of the U-boat war near its peak in the Atlantic, and the failure of Wavell’s June 1941 Battleaxe thrust in the Desert. On 7 July, the Air Staff Ops Training work took Bob Bateson back to HQ RAF Middle East. There was to be little flying for some time, apart from a rather au revoir flourish on 26 July 1941. That morning he converted F/Lt Cliff on to the Mark IV Blenheim: Cliff was then duty pilot to none other than Air Chief Marshal Sir Edward Ludlow-Hewitt KCB DSO MC, Inspector General of the RAF. Thereafter, August, September and October passed with flying “Nil”. His service flying time at that point totalled 1291:15 hours, having add barely 47 hours since February 1941. Perhaps it was in this period that he had a close encounter with an Italian booby-trap bomb. Temporarily blinded, he later recalled being flown to Cairo and classified “unfit to fly”. His vision improved with daily treatment and he resumed flying. After nine months off operations, Bateson returned to the Desert. On 26 October he was posted in the rank of Wing Commander as SASO to 270 Wing, under Grp Cpt Beamish at Fuka. Preparations were well in hand for Auchinleck’s Crusader offensive. From 18 November, Eighth Army troops and armour surged forward deep into Libya, supported by the Desert Air Force. As Senior Air Staff Officer, liaison and operational awareness were right up Bateson’s street. To be on the spot, he took once more to the air, often enough by Hart or Audax for shorter trips with one passenger, or by Blenheim with larger groups. His first flight after the long break, on 6 November, was to pilot Blenheim IV Z9609 from Fuka satellite to Heliopolis with Sgt Hughes and three passengers, returning to Fuka satellite two days later. Wing HQ had moved to Gambut on 18 December. On two occasions, with Grp Cpt Kellett aboard, Bateson was able to take part in operations again: in Blenheim IV T2249 for a raid on Bardia on 17 December; then ending the year with real dash—a mid-day sortie on New Years Eve in Hart K6424, Kellet in the back seat, flying a recco of Bardia at 2,000ft during an attack. “Having a look!” The operations count now stood at 68. By then, a new element had already entered the war equation: on 7 December Japan had attacked Pearl Harbour and Malaya. To 211 Squadron His posting orders came on 6 January 1942, to command 211 Squadron. They were already at Helwan, re-equipping and getting up to establishment, this time as a 24 aircraft Squadron, bound for the Far East to fight the Japanese: a Wing Commander’s post. On 9 January, Hugh Clutterbuck apparently flew out to Gambut in a Mark IV to collect him—certainly Bateson flew the anonymous aircraft back to Helwan, noting one F/Lt Clutterbuck as 2nd Pilot or Passenger. In his later recall of the Italian booby-trap injury to his eyesight, Bateson associated his recovery with an unofficial test flight in a 211 Squadron Blenheim at Helwan on taking command, however, his recall sits at odds with his flying record. Nil flying hours from August to October 1941 then, in the first week of January 1942, almost daily flights made before leaving 270 Wing, immediately followed by the flight to Helwan on 9 January. Five days later, he was flying again, a 40 minute aircraft test in Mark IV Z9649 with “Capt Bloomfield and crew”, presumably SAAF personnel. By the third week of January 1942, Rommel was back on the offensive. Bateson was very busy at Helwan, working hard to get his Squadron ready for the testing move to the Far East. Together they faced a journey of some 6,000 miles, whether by sea or by air, to take up operations. At this point, the next entry on the Duty page records “Posted to Command No. 211 Bomber Squadron and Move to Far East” The three corresponding entries in the Record of Service table, that most valuable reference in Flying Log Books of that period, hold much of interest.