|

Flight Lieutenant JF Luing 121527 RAVR died in captivity 1944

John Frederick (Jack or Johnny) Luing was the elder son of James and Dorothy Luing of Elsenham in Essex. Jack’s story and that of BB “Barney” Mearns (a Navigator of 211 Squadron) and of Don Lomas (of 159 Squadron) are intimately connected.

The India & Burma casualty roll, with its 8 March 1944 “missing from operations” entry for F/Os Luing and White first drew forth correspondence with Matt Poole, whose mother’s first husband Sgt G Plank 1435434 (also of 159 Squadron) had died, shot down in a Liberator over Burma on 29 February 1944. Lomas, Luing, Mearns and White had all been held PoW in Rangoon Gaol: Luing and White did not survive. Matt Poole was already in contact with Don Lomas, whose vivid interviews were the basis for my original compilation of this page.

Later, having spotted the 211 Squadron site and this page, Jack’s brother Peter Luing got in touch with me. The Luings’ second son, Peter also served in the war as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm. In the course of a very kindly correspondence, Peter and his wife Tessa have gone to considerable trouble in making treasured family memorabilia available to me for the 211 Squadron history, with some fine photographs of Jack and a remarkable letter from Navigator BB Mearns.

Here I have taken both personal background, the 211 Squadron Operations Record Book and the Luing family photographs to add a fuller picture of Jack, before turning to Don Lomas’ telling account of their captivity and Jack’s death. Barney Mearns’ letter on these matters was of equal moment—being the account of a 211 man, it has been accorded its own place.

Jack Luing has thus emerged more clearly from the mist of the past, thanks to Peter and Tessa, and to Don and Matt. Together, the narratives of Don Lomas and Barney Mearns provide compelling insight into the steadfastness of men in the direst adversity.

Jack Luing

Jack had started flying just before the war with a University Air Squadron at Derby. Joining the RAF Volunteer Reserve, at the outbreak of war he was called up for active service.

Early days (Luing collection)

Pictured in RAFVR airman’s uniform: no rank badges or wings here, other than the side-view glimpse of the forage-cap airman’s badge. The cap, known variously as the “field service cap”, the “duty cap” and other variations including the colloquial “fore ‘n after”, was worn by officers and men alike, the main distinction being the badge on the left side of the peak: a crowned eagle for officers, and the round RAF wreathed monogram for men.

JF Luing: Pilot Officer (Luing collection)

After a lot of square bashing at Hastings and flying training, he gained his pilot’s wings, a Pilot Officer’s commission and uniform with gilt VR lapel badge in place of the airman’s cloth shoulder patch. Tinted black and white photographs were quite favoured then, and this is a good example.

In time, Jack found himself posted to 604 Squadron, a night fighter unit with radar-equipped Beaufighters. At that time the Squadron CO was the well-known night-fighter ace, the late John Cunningham. Jack later transferred to 137 Squadron, then newly formed and flying Westland Whirlwinds. A spell with the USAAF flying P.38 Lightnings non-operationally was followed by a return to 137 Squadron at Manston.

Jack and Estelle’s wedding August 1943 (Luing collection)

Peter Luing FAA far left, Jack and Estelle Luing, centre. After Jack married his Tess (Estelle Joan, née Trott) in a late summer wedding, there was time for their honeymoon and later, a short home leave.

Then, around the middle or end of September 1943 Jack was posted to India, where 211 Squadron had re-formed on 14 August at Allahabad, to work up with Bristol Beaufighter Xs before resuming operational status in January 1944. In entering the Burma offensive, the Squadron then moved forward to Silchar West in northern Bengal on 8 January 1944. Jack joined them on that very day.

At that date the Squadron’s initial equipment appears from ORB entries to have been 16 Beaufighters with 27 pilots and 26 observers on strength. The Squadron also retained two miserable Bisleys (BA990 and EH507) on charge, apparently as “hack” transport. In reaching the Squadron at Silchar, Jack may well have been collected from Ranchi in EH507’s trip that first week of January.

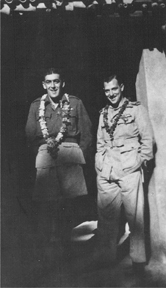

JF Luing on the right, India, probably early 1944 (Luing collection)

With an unidentified pilot (perhaps a Flying Officer, possibly a Pilot Officer).

Jack Luing in Bengal early 1944 (Luing collection)

Jack Luing as Flying Officer in India early 1944 (Luing collection)

211 Squadron personnel early 1944 (Luing collection)

The three on the right are pilots, and wear the single ring of a Flying Officer on their shoulder boards (Jack Luing is last on the right). The fourth man, far left, has no aircrew badge, but is also apparently a Flying Officer. The same man appears third from the left in the group below. These two photographs seem likely to have been taken together.

211 Squadron aircrew early 1944 (Luing collection)

Three F/O pilots and a fellow, non-pilot officer (third left, who also appears in the group above). The Flying Officer on the far left is also the subject of the following photo. Some traces of a double exposure are visible: this may be the first photo of the roll.

211 Squadron pilot early 1944 (Luing collection)

The same unidentified Flying Officer pilot. It does not seem to be F/O Alf Waddell, though he was a particular friend of both Barney Mearns and Jack Luing. Perhaps Jack’s relaxed companions may be identified at some point.

By 1 February 1944 the Squadron had moved to Bhatpara in what was then central Bengal, permitting operations deeper into Burma. As used operationally by 211 Squadron, Bhatpara was about 60 miles southeast of Dacca in what is now Bangladesh. Today, there is also a Bhatpara north of Calcutta.

Jack was two months on operations, then in March 1944 the Squadron suffered a period of heavy loss with 10 aircrew (and five aircraft) missing. The last entry recorded in Jack’s Log Book was for 8 March 1944, possibly for an air test. The ORB Form 540 (daily) that same day records his loss on a ground attack operation:

Bhatpara 8th March 44. Weather at base fine and clear.

‘E’ LZ229 F/O Moffatt, F/Sgt Morris A/B 08:50 landed 12:53

‘H’ LZ116 F/Sgt MacDonald, F/Sgt Freeman A/B 08:50 landed 12:53

‘R’ LZ364 F/O Luing, F/O White A/B 09:18 Missing

‘T’ LZ360 F/Sgt Bell, F/Sgt Nash A/B 09:07 landed 14:41

TASK: Aircraft ‘E’ and ‘H’ to attack railway communications Mandalay—Lashio

Aircraft ‘R’ and ‘T’ to attack road communications Pyawnggawng—Lgok—Thablikkyin

‘T’ and ‘R’ attacked road bridge at Kwanmawk with 80 [sic: 8 each] 60lb RPs. No claims of damage were made as results were very difficult to see. Bridge also strafed with 20mm cannon. On the remainder of the route no movement of any kind was seen.

MISSING: Beaufighter LZ364 Pilot F/O JE Luing RAF [sic] Nav F/O GJ White RAF

The railway attack pair had better luck. Although chased by seven “Oscars”, only aircraft ‘E’ was damaged and both ‘E’ and ‘H’ returned safely, as did ‘T’ from the road sortie. Jack Luing had been promoted to Flight Lieutenant so shortly before that Operations Record Book and other references to his loss had not yet caught up with his advancement.

Of the 16 aircrew of 211 Squadron held prisoner in Rangoon Gaol, Jack Luing was one of the four who did not survive. It was a year or more before Dorothy and Estelle were to have the sad news of his death in captivity.

Don Lomas

Matt Poole's reportage of Don Lomas’ narrative, concerning the death in captivity of 121527 Flt Lt John F Luing, 211 Squadron RAF, Rangoon Gaol, 24 October 1944.

Matt, a resident of Maryland, came across the 211 Squadron site while searching for Rangoon Gaol information. He, too, has spent a long time searching and compiling, as he readily explains. Along the way, as such things go, he has come to share a close friendship with Don Lomas.

Shot down on a 159 Squadron Liberator operation over Burma, Don was in turn the companion in captivity of John Luing, until John’s death. For those unfamiliar with the conditions PoWs in Burma experienced under the Imperial Japanese Army, Lionel “Bill” Hudson’s Rats of Rangoon may also be of interest.

Don Lomas and two other survivors of his crew in Calcutta (D Lomas)

Taken soon after release from Rangoon Gaol. From left: Norman Davis, nurse, Jack Harris, Don Lomas. Norman and Jack died within a year of one another in 1970/71.

Matt Poole’s introductory notes

“My mother's first husband was an RAF 159 Squadron wireless operator/air gunner lost with his Liberator crew over Rangoon on the night of 29 Feb 1944. A pair of Oscars piloted by aces Bunichi Yamaguchi and Hiroshi Takiguchi of the 204th Sentai had caught this bomber from behind as it was coned by searchlights. A second 159 Squadron Lib was also shot down in a like manner by the same two Oscars, but six of the nine crewmen baled out and were captured.

Two died in Rangoon Gaol, but four were liberated from the camp. For 12 years [ie since 1990] I have delved into this air combat and its aftermath, with many amazing finds. My hunt continues as a labor of love. I think you can understand such a project perfectly well. Of those four Liberator airmen who survived until liberation, only one is still alive today: Don Lomas of West Yorkshire, UK. The reason I'm writing to you now is because your site answered some questions about the man who was in a solitary confinement cell with Don at Rangoon Gaol until he succumbed to dysentery: 121527 F/O Luing of 211 Squadron. From information on your website I now know that Luing flew for 211 and was lost on 8 March 1944.

The excerpts that follow [...] come from a number of interviews with Don. We talked over this subject on several occasions. [...] In 2000 a friend shot some video footage of graves at Rangoon War Cemetery. I asked her to videotape Luing's grave. The rank on the grave is higher than Squadron records indicate. The grave marker reads:

FLIGHT LIEUTENANT J. F. LUING

ROYAL AIR FORCE

24TH OCTOBER 1944

“I GIVE UNTO THEM ETERNAL LIFE”

ST JOHN X.28

[The Rangoon War Cemetery is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, and John Luing is further commemorated on the CWGC Honour Roll.

The contributions of Messrs Lomas and Poole to this moving narrative have been much appreciated. What follows is verbatim, my few amplifications shown as here.]

The transcripts

Part 1

D [Don Lomas]: I'm not sure...For the longest period we were here in what used to be called, supposed to be the isolation, single cells. There were three of us in each one. They were supposedly in peace time (single cells). We had a Mosquito pilot [sic: Beaufighter - a very understandable slip] in with us, Davis and me and this other chap. We were there for six months. And this ...names, names. He was shot down in northern Burma in a Mosquito doing low level attacks on river boats. The Japs put a cable across from trees.

M [Matt Poole]: That's how Hudson and his navigator came down.

D: Anyhow, he and his navigator travelled down by bullock cart to Rangoon in about a week. And along the way they ate native food and they developed amoebic dysentery. It wasn't uncommon on the squadron, really. But in hospital you'd get sulfa treatment which would kill this amoeba. And of course he had no treatment at all, and he was gradually worse and worse. Johnny. And one morning I'd waken up and he'd died. And he laid there like...Terrible. And I've never forgotten we didn't tell the Jap guard until he'd been around for breakfast, because it was an extra tin of rice. First thing we thought of. It shows you what sort of condition you get in. Food. So hungry. We used to get a little square tin of rice. Chinese prisoners brought it round with a Jap guard, in big wooden barrels. One with tea - we called it tea: hot water with a leaf floating round, and rice. And I remember saying to Davis, "Say nothing, till they've been around." So an extra drink, an extra....We got that way, I'm afraid.

M: If I were going to die in that situation, I would hope that something good would come from my death. And that's something very little: that it came, extra rations.

D: Johnny Luing. It's just come back to me Johnny Luing. He'd only been married three months when he came abroad. And another thing, in daylight raids he'd only had shorts and a bush shirt, a sleeveless shirt, you know. And at night he got cold. And one of the Japs took pity on him and found him a blanket, because there was no bedding of any kind. You just laid down on the floor. And he found him a blanket, and I've never seen so many lice. It literally crawled.

Part 2

D: ...In this cell in the Rangoon City Gaol (Law Courts) that I shared with Norman Davis and a chap, Mosquito pilot called Johnny Luing. He died in there. Was taken prisoner up north, doing low level riverboat shoot-up, hit a cable across river. This Luing came down, he travelled down on bullock carts from somewhere. It took about three days, and they had to eat native food on the way down, and they all developed this amoebic dysentery, you see. And his navigator had already died. And he passed away around Christmas, around New Years Day, I think. He shared the same cell with Davis and me, didn't he. Went down to nothing. And he could have been down in a hospital, no problem. It was a fairly common complaint out there, amoebic dysentery. He'd only needed a bit of proper medication and he'd be alright.

Part 3

D: We used to get little square tins, one with rice, and one with...The Chinese would come around, one with rice, the other with a bucket of tea, probably tea. It was hot and wet, that's all you could say. Perhaps a green leaf or two floating in it. But it tasted really good, believe me. That's all you were going to get. And you got the rice, the tin, and that to drink in the morning, and that had to last until about 4 o'clock in the afternoon. You got a similar thing then, and that was it until the following morning, you know? But we survived. I'll never forget, which I've often thought about it, was this chappie which died with us in our cell. First reaction: don't send for the guard till they'd been here with breakfast. Davis and me. An extra breakfast that we shared.

M: It was the right thing to do.

D: Of course. Yes.

M: Survival... That man wouldn't have wanted to cause...

D: ...If anybody died, you call out, and a guard, and it was early morning before a guard appeared. And he had a filthy old blanket, one of the guards had taken pity on him because he had no clothes, and he'd found him this blanket which was full of lice, but he was glad of it. Keep him warmer in the night. He was covered up with this blanket, and I realized he was dead. And said, keep him covered up till the guard came around with the Chinese and looked in, you know, the usual. Three tins outside, with the rice and three drinks, until the next meal.

M: Life sustaining food.

D: I know, yes, I know. Poor old Johnnie. And he'd only been married three months. Johnnie, he shared the cell with Davie and me, Davis. And he was shot down up north, and he contacted this amoebic dysentery. And the last few days that he lived, he was passing blood. It's an amoeba which attacks the bowels, you know, and the system is eaten away.

M: Oh, the pain.

D: Yes, that's right. Poor Johnnie. Nigh three months.

Part 4

D: They survived, but the only time you could see them was when you walked past the cell, which the three of us in the cell, I was the only one able to carry this box out, which was the sanitary bucket, the benjo. It was a .303 ammunition box, a little box, with the centre part, just a little square in the centre, which you sat on. And that was it. And it leaked. And it had to be taken out, and Davie, his feet were terrible. And mine were...I had to walk on the sides of me feet. My feet all came up in blisters. Just a condition. Yellow blisters all on the soles of the feet.

M: From diet?

D: Yes, a condition. Lack of vitamins, and that sort of thing. And John Luing, he wasn't strong enough to stand up, hardly, so I was the only one. I used to go, and I could glance in at these cells, as you walked past, you see. The way out was about halfway down the length of the block. Then an outside door took you outside. I used to go out and empty this latrine into some containers, which they used later to plant potatoes. Considering half the people in the ward had dysentery, and then they were planting potatoes in that, you know, how the hell we didn't all die off I don't know! (Chuckle.) There was no hygiene. I didn't have a wash for 12 months. I never had a wash. I wore the same shirt day and night.

M: And it didn't rot away on you?

D: Fortunately it was an issue. Thick, heavy, typical British overseas issue. I was lucky that I had the clothing because we were on night operations, and you had to wear a lot of clothes because it was cold. I had a battle dress, and a sweater, which I used as bedding, to lay on eventually. I was lucky, because lots of them had their uniforms taken off of them. You know. Anything the Japs wanted, they took it, you see? And John Luing who was in with us, he'd been on daylights, low level, and he only had shorts and a sleeveless shirt, and that's all he had you see? So he suffered. I was lucky with clothing. I was. Dear, oh dear.

Part 5

Question 25: Who were your cellmates in Block 5? Norman Davis? Westermark, King, or another crewmate? Dudley Hogan or someone else not from your crew?

Answer: Norman Davis and an officer called Luing. He was a Mosquito [sic] pilot. He and his navigator were shot down and taken prison while attacking river craft in northern Burma. A Jap guard brought them down to Rangoon by bullock cart. Three to four days of a job. They were eating native food, and as a result, amoebic dysentery. Quite easily cured, with proper medical attention, but of course this wasn't available. The navigator had already died, and Johnny succumbed about Christmas time.

Part 6

D: Something that I escaped, fortunately, was malaria. To start up with malaria, that was a thing. And that cap you’ve shown me a picture of tonight (the RAF-issue survival hat-with-mosquito netting which Don wore as a PoW and still has), I think that was largely responsible for me not getting malaria. Because I was covered up, otherwise. Luckily I had clothing. I had the shirt I was shot down in, and I wore it every day and night from then on. And how it didn’t drop in shreds, I’m surprised. It must have stunk horribly. Sweating when it was hot, and cold at night. And I still wore the darn thing. It was an issue one, fortunately.

M: For aircrew. Heavy.

D: Heavy-duty stuff, you know.

M: As opposed to Johnny Luing. Low altitude (when he baled out and was captured).

D: Oh, he was in shorts and (lightweight tropical dress). Slightly bare, and he suffered for that.”

Afterthoughts of M Poole 2004

“Don Lomas [...] is quite well and chipper. I last saw him on 28 February 1998 at the memorial service we held in London's St. Clement Danes church for the two 159 Squadron crews shot down on 29 February 1944. Don, the only crewman alive of the four from his aircraft to survive imprisonment, in a hushed church filled with about 140 people, walked the length of the aisle to the altar to place a wreath in homage to his fallen mates. With Don standing before us, facing the altar, a brilliant London trumpeter blew the Last Post, followed by a minute's silent reflection, and then followed by the uplifting trumpeting of Reveille (not the American "get out of bed" military bugle tune of the same name). We all marvelled at how this wonderful survivor of so much suffering could stay on his feet during such an utterly powerful moment.

[...]

A couple of other notes about the Lomas recollections. Davis (also called Davie) was Norman Davis, Don's flight engineer. There's a picture of Norman in the softcover edition of The Rats of Rangoon, by Lionel Hudson (senior air force POW). The photo shows Hudson, Davis, and four or five others standing at the door of the Dakota taking them to freedom in May 1945. Davis is at the bottom of the ladder. It is a wonderful photo representing the joy of freedom. Actually, you can see this on the Australian War Memorial website by searching on Lionel Hudson or Norman Davis in the photo section. And you will note in Don's recollections that he believed Johnny Luing died around Christmas. Here Don is wrong by two months, but it must have been so difficult to keep months straight when your existence was the same dreadful routine in solitary confinement day after day, week after week.”

The sum of things

Don Lomas, after surviving the loss of his aircraft and brutal captivity in Burma, was repatriated to the UK and returned to civilian life. He enjoyed a long and fulfilling life at work and with family, to die at age 92 on 15 October 2008.

Sources:

211 Squadron Operations Record Book RAF Form 540, Form 541 AIR 27/1303

Personal correspondence M Poole/D Clark

Personal correspondence P Luing/D Clark

Personal interviews M Poole/D Lomas

D Lomas diary collated M Poole via R Quirk website

www.211squadron.org © D Clark & others 1998—2025

Site created 15 Apr 2001, last updated 24 Dec 2025. Page created 4 Jul 2004, last updated 26 Jan 2010

Home | Site Summary | Next | Previous | Enquiries | Glossary | Sources | Site links | Do it yourself | Site updates | Site Search

|