|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1684520 F/Sgt Ronald C Kemp RAF 1922—2014 The narrative of Ron “Kempie” Kemp, Flight Sergeant and later Warrant Officer of the Royal Air Force in the Burma theatre, Navigator/W to Monty Walters of 211 Squadron RAF. By mid-1944 Ron Kemp had achieved his Navigator’s wing in the RAF and was about to be posted to the Middle East for Beaufighter operational training. He proposed to Pam and they decided not to wait. They married on 5 April 1944. Around 1995 and by then grandparents, Ron and Pam decided that they should make a record of the way life had been for them in “the good old days”, to pass on to their growing family. It was soon clear that hand-written manuscript notebooks wouldn’t do the job, so they took on the computer age. For all the many happy years they had spent together, they gave their narrative an apt title: Who Could Ask For Anything More. Safely recorded on PC, Ron ran off copies of their story for interested readers whenever he had a moment to spare in caring for Pam in her increasingly frail health. Sad to report that Pam Kemp departed this life on Saturday 21 September 2008. She will be much missed.

Ron and Monty had trained together on the Bristol Beaufighter in the Middle East before their posting to 211 Squadron. They remain in close touch. Between them, they dug very generously into their rich collections of Squadron material after Monty contacted me late in 2007. Quite typically of the 211s, both men said the same thing: if I thought any of it was of interest, I was to use as much or little as I liked. For Ron’s two chapters on the India & Burma period from the Kemp family narrative, I’ve added a couple of small amplifications in the usual way [thus], left one short passage aside, and made some minor changes to layout. The photographs are from those selected to match the story by Mont, from his own collection, either with his captions or mine, and with my commentary [thus]. Here then, is Ron Kemp’s account of 211 Squadron life, from Who Could Ask For Anything More. Chapter 11: We Trained—and Trained Again His body had been in the water for a couple of weeks and was obviously quite distended when found. Consequently the coffin was very large and when we got to the graveside the padre said he thought it would be too large for the grave which had been prepared. The Flight Lieutenant in charge—a rather jovial type and not at all suitable for a funeral—solemnly measured the width of the coffin with a crowbar and compared it with the grave. It was too wide. The padre said that they could get the grave made wider but it would take time and were we prepared to wait. The alternative, he said, would be to put the coffin in on its side and did the Flight Lieutenant think this would be all right. They eventually decided that this would be the best thing to do especially as by now the pall-bearers and the rest of us were almost overcome by the smell emanating from the coffin. And so the poor lad was finally laid to rest. I have often thought what a blessing it was that his parents weren't aware of the precise circumstances. From Poona we were posted to the Ground Attack Training Unit at Ranchi. We were here to do low level flying and ground attack since it was now evident that this was the Beaufighter's role in the Far East. Our training programme consisted mainly of rocket and cannon firing at ground targets but for the navigators there were low level cross country exercises by day and by night. And we were soon involved in the usual catalogue of accidents. Shortly after we arrived a Hurricane pilot from our billet lost himself while flying an exercise, ran out of petrol and had to force-land. He went through the windscreen, broke his thigh, and died two days later in hospital. A Beau with two pilots aboard crashed on the rocket range and they were both killed. Soon afterwards another Beau flown by a Canadian we all knew crashed on the range in flames and he was killed. This all happened in the first week and we began to view the course with mixed feelings. On our course one of our pilots swung on take-off and narrowly avoided a crash. On his next trip he hit a tree while low flying. Not to be outdone, Vic Seaton, a good friend, then hit two trees and came back with a couple of branches and a dead chicken in his wing!

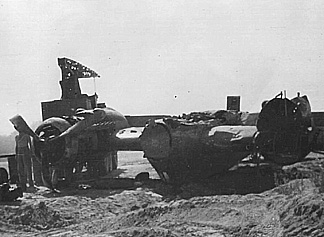

[This 27 Squadron Beaufighter swung on take-off and overturned, without casualties. Under the combined urge of its two Bristol Hercules engines, the Beaufighter needed care and skillful handling of throttle and rudder at take-off, to balance engine power with rudder authority as airspeed rose.] Somebody else had an engine cut out at night and had to make a single engine landing—not easy in a Beaufighter. A Hurricane force-landed on the range—the pilot was unhurt but was removed from the course for carelessness. And the news from the squadrons wasn't very encouraging either. There were three Beau squadrons being supplied with crews from Ranchi and they seemed to be losing crews at an alarming rate. I wrote in my diary "Any time now we leave for a squadron and I don't mind admitting I'm scared stiff." I realise that I have not said anything so far about the ubiquitous cha-wallahs. These were an institution in all the service quarters in India and were always on hand. They would squat on the floor with their portable urn of tea—often carried on a yoke across their shoulders—and dispense mugs of tea to all and sundry at a few annas a time. The refinement of this at Ranchi was the supply of fried egg sandwiches otherwise known as "egg banjos." These consisted of a fried egg in a soft roll and were cooked and assembled at the bottom of one's bed and they were utterly delicious. Looking back, however, I don't think they could have been very hygienic! On 10 March 1945 we finally left Ranchi and started on our journey to the squadron. En route we had three days in Calcutta where we saw all the extremes of poverty and wealth that we had already seen in Cairo but with many more uniforms in evidence now that the war effort was beginning to be concentrated more towards the Far Eastern theatre of operations. From Calcutta we travelled by train to the river Ganges and then we had an eight hour trip by river steamer to Chandpur. From there to Chittagong, then via the Arakan road to Cox's Bazaar and finally to the airstrip at Chiringa in Assam just across the border from Burma. We arrived at Chiringa on 18 March 1945 and were allocated to 211 Squadron. We had a joyful reunion with many of our friends who had gone before us and then settled in to our billets which were huts—or bashas—made of cane and bamboo. There was literally nothing at Chiringa except the airstrip.

There was a small native village which was out of bounds and the only leisure facilities were the camp cinema [opened the day after Monty and Kempie arrived] and the mess. Beer was rationed and all in all there was very little to do. The weather was extremely hot and I seem to remember that we spent quite a lot of our spare time just lounging around on our beds reading.

[211 Squadron aircrew relax over books and letters by the light of a hurricane lamp. If names may slip away over the passing of the years, faces remain familiar]. We soon learned that the role of the squadron was to harass the movement of Japanese troops and supplies on the ground. For this purpose the Japs were using trains, lorries and river vessels including native sampans which were small wooden sailing boats. It was going to be our task to patrol roads, rivers and railways and to attempt to destroy anything we saw moving. These patrols were to be carried out at a height of about fifty feet and the Japs were in the habit of stringing tripwires across the rivers, roads and railways at approximately this height. They were also very effective with light machine gun fire against low-flying aircraft and for all these reasons it was essential to keep a sharp look-out. Eager as I had once been to become aircrew and later, to get on to Beaufighters, I was now beginning to wonder what I had let myself in for! An appropriate moment, I think, to start another chapter to deal with our operational efforts. Chapter 12: Whispering Death We started out on 23 March with some local familiarisation flying and rocket firing practice. Two days later we went on our first operational patrol, flying as number two to an experienced crew. We went out over the sea and down the coast of Burma at two thousand feet dropping to fifty feet as we came in over the coast to patrol the Bassein delta in the southern part of the country. The delta was an extremely complex network of rivers and streams and a map-reader's nightmare and I was thankful that I was not navigating on that occasion. My log book contains the report "No movement seen" followed by the words "First safely over!" After all that training we were "on ops" at last!

[First sortie, 25 March 1945. A climbing turn to starboard, departing the Bassein Delta in the loose formation that left them ready for any eventuality, from mutual support to independent action. And a “first and last” shot: Monty leading on their first sortie with Kempie taking the snap from his Nav/W cupola, of W/O Johnny Birch and his Nav/W F/O Allan Carter on their last patrol, tour about to complete. Although Birch’s subsequent movement seems not to be recorded, Carter went on to a posting with 224 Group AHQ in the War Room.]

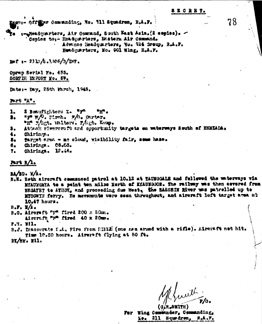

The Sortie Report of their first operation. 4 hours in the air for 35 minutes patrolling the waterways South of Henzada and “No movement seen throughout”.] Four days later Mont and I set out on our first solo trip. We were first required to fly [about 150 miles] South to Akyab Island to pick up six thousand leaflets which we subsequently dropped between the Burmese towns of Taungup and Gwa. The leaflets were intended to persuade the Burmese not to co-operate with the Japanese but they were printed in a very primitive fashion and I doubt whether they did the slightest bit of good.

Pilot’s Log Book F/Sgt ME Walters 1 April 1945: Beau X RD196. Pilot Self. Nav/W F/Sgt Kemp. Briefed patrol Bassein—Kyangin Railway. Patrol same. 1 Loco hit plus 8 rolling stock. Nav to drop leaflets over towns etc. Time 3.00hrs day 1.45hrs night. Totalhrs 4.45. [RD196 is logged as a 27 Squadron aircraft in Halley’s RAF Aircraft PA100—RZ999. In April 1945, the Flying Elephants were leaving Chiringa for Akyab. The two Squadrons had spent some time in close quarters. RAF aircraft records of the Middle East and Far East survive only in an imperfect and very partial state. We then went on to patrol the waterways south of a town called Henzada where we attacked and damaged some river craft. We returned without mishap. My log book does not record how we felt on our return but I think we must have felt pretty damned good! After all, I had managed to get us there and back without getting lost and Mont had managed to get us off the deck and down again in one piece and to fire his rockets as well! Incidentally, it will have become clear by now that for all the sophisticated training in navigation techniques that I had undergone at Navigation School—dead reckoning, radio and astro-navigation—all we were actually doing was map-reading, which was fine as long as you could see the ground and there weren't too many confusing features.

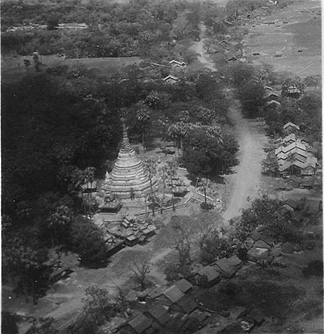

[There may be a lone cyclist on the road opposite the temple. The Beaufighter patrols were so effective in suppressing movement that by 1945 somewhere between a quarter and a third of daylight sorties returned to report “no movement seen”, as in this case.] On 1 April we patrolled the railway line between Bassein and Kyangin. We were lucky enough to find a train—the dream of all low-flying aircrew—and this was attacked with both cannon and rockets. This involved the pilot pointing the aircraft at the target, going into a dive, releasing the rockets, firing the cannons and remembering to pull out before hitting the deck (it was also as well to remember that the Beaufighter tended to wallow a bit in a dive so that it often finished up a bit nearer the ground than had been intended!).

[The human cost of the Burma Railway only became apparent to the Squadron later. Here, it is just a tempting and potentially dangerous target.] I also joined in the fun by firing my single Browning machine gun from the rear cockpit as we pulled away. This had a small metal projection in the mounting in line with the tailplane. This lifted the gun slightly as it traversed and—hopefully—eliminated the possibility of shooting off your own tailplane. A bit of a Heath Robinson device but fortunately it seemed to work! My log book records one locomotive and eight rolling stock damaged although we were not lucky enough to achieve a "flamer." We returned safely to base in just under five hours. We next flew on 5 April which happened to be my first wedding anniversary. We were briefed to patrol the notorious Ye to Tavoy road which was well south of Rangoon and down towards the Malay peninsula. It was notorious because the Japs had a number of light anti-aircraft machine guns stationed along it and it was also a bloody long way to fly! We set out at 6 a.m. and flew down over the sea coming in over the coast to Tavoy at the southern end of the road. We commenced our patrol at low level and saw no movement on the road at all. We were nearing Ye and the end of the patrol area when I heard a noise which sounded like ball-bearings being dropped into a metal bucket. This was followed by a loud clang and we knew that we had been hit by something. There was no visible damage and Mont could not detect any change in the performance of the plane but we had no way of knowing whether there was anything wrong and we were a long way from home. We crept back not knowing whether one or both of the engines were going to pack up at any minute. It was a long journey home! We finally made it after a round trip of seven and a quarter hours and got down safely. I could have kissed the tarmac if it hadn't been so hot and sticky—especially when the mechanics removed a .5in bullet from the port engine. Fortunately for us it hadn't done any serious damage. After this adventure our next three or four trips seemed rather tame. We patrolled roads, rivers and railways in the south but saw very little movement. On one occasion we had to turn back because the weather was bad—the monsoon season was approaching. We fired some rockets into a railway line just to give the Japs something to think about but on the whole things were very quiet. I had to alert Mont once or twice to the fact that there were some very tall trees around and I know that he still remembers my shouted warning, "Pull up, son, there's a tree ahead!" because it became a sort of catch-phrase between us.

[Attack on a Japanese steamroller at Akyab air strip. The Mark X Beaufighters in Burma generally carried a camera in the extreme nose. Here, the aircraft is below the tree-tops some three hundred yards away, as cannon shells strike the target to raise smoke, dust and debris above wall height. At 250mph those trees are about three seconds away. Has Mont noticed them yet as he concentrates on the target through the reflector sight, or is Kempie already calling their warning over his shoulder?] Life in camp was very humdrum when we were not flying. We spent a lot of time at the camp cinema but about the only film that I can remember is "Bathing Beauty" when Esther Williams was all the rage. On one occasion we went out on a shooting party taking shotguns and several young men from the local village to act as bearers. We managed to shoot a few birds of unidentifiable—possibly now endangered! —species and at the end of the day we offered our "bag" to the young men who had helped us. But they weren't having any old dead birds—they wanted money and in the end we had to pay them off. The thing that I remember most clearly about that outing is that one of my shots winged a bird but failed to kill it. The bearers brought it to me and I couldn't see it suffer so I had to wring its neck. Never again! I also remember being able to pick very large mangoes straight from the trees at the edge of the airstrip. Another memory is of coming out of the mess after dinner and seeing a large flock of vultures waiting for the scraps to be thrown out from the cookhouse.

One or two things that perhaps I should have mentioned before about flying in Beaufighters. The navigator sat in a rear cockpit and was separated from the pilot by fixed ammunition boxes which supplied the twenty millimetre cannons. Although it was possible to communicate using the intercom there was a feeling of being separated from each other which could only be overcome by the navigator climbing over the ammo boxes with a good chance of throttling or rupturing himself when his parachute harness caught on some protrusion on the aircraft. Incidentally, parachutes would only have been useful to and from the patrol area at two thousand feet—they would certainly not have been much good at fifty feet because there were no ejector seats in those days. And one of the other problems was the extreme heat. The aircraft stood out in the open in blazing sun and consequently it was like climbing into a furnace. The smell of aviation fuel was overpowering and one had to climb in taking care not to come into contact with any metal either outside or inside because everything was almost red hot. We always had to be prepared for a forced landing behind enemy lines although one doubts whether it would have been possible to survive. We flew in trousers—not shorts—and long sleeved shirts in case of an aircraft fire and to protect us from mosquitoes and other insects. We carried a water bottle, a revolver, a Commando knife and our escape kit. The latter was a rather elementary collection of items and included tea tablets, a tube of condensed milk, aspirins, iodine, benzedrine tablets, water purifying tablets, a fishing line with hooks, a small compass (sealed in rubber for secreting in an appropriate aperture in one's anatomy!), a razor blade for dealing with snake bite, a leech stick, a small telescope and a very primitive-looking wooden comb with a metal saw blade built into it. There was also another small compass in the form of two metal trouser buttons. These were supposed to be sewn on to one's trousers until needed when they were to be ripped off and mounted one on top of the other to point to north. Very fortunately we never had to use any of it. I still have a collection of some of these items. On the evening of 30 April we were part of a small force briefed to locate and destroy a fleet of motor launches reportedly seen in the estuary of the Rangoon river south of the city. The Japs were being beaten back in Burma and were in retreat towards the Malay peninsula and Singapore and were using whatever transport they could to achieve this end. We arrived in the target area at dusk and about a dozen aircraft were milling around in the half-light looking for the launches. The only thing that Mont and I could see was the boom ship which was supporting the antisubmarine and torpedo net across the mouth of the river and we went down to have a go. Our rockets were spot on and the vessel burst into flames. By now it was getting even darker and it was clear that there was a real danger of mid-air collision. Mont and I agreed that it was time to get the hell out and we headed for the coast as fast as we could. This would have been fine except that we were right at the start of the monsoon season and as soon as we got over the sea we were confronted by enormous banks of cumulonimbus cloud. We knew from our meteorology lessons that flying through these clouds was not recommended since there could be up-currents of a hundred miles an hour which could literally tear an aircraft to pieces—and had frequently done so. So we tried to climb above them but the higher we climbed the more they seemed to tower above us. We had no oxygen supply and at about twenty five thousand feet we gave up (the maximum height for a Beaufighter was only twenty six thousand five hundred feet) and spiralled down in an attempt to get under the cloud base. This was also a very dangerous manoeuvre because owing to changes in air pressure caused by the weather we had no way of knowing whether our altimeter was recording anything like our true height. It was pitch black all around us and I remember being very scared because I was convinced that we were going into the sea at any moment. Mont has since told me that the time he spent flying solely on instruments that night—an hour—was the longest that he had ever done. This was one of the occasions when I willingly climbed over the ammo boxes because I didn't want to be alone in the back of the aircraft. (The other occasion was when we were hit by anti-aircraft fire on the Ye to Tavoy road.) We eventually managed to get under the cloud at what we thought was about three hundred feet. We will never know how close we may have been to disaster that night. After a while we were able to gain some height and to establish contact with the radio station on Ramree Island which was on our route home. We called them up and they were using a call-sign that night that I shall never forget—it was such a relief to hear a very bored voice reply "Hallo, this is Silly!" We eventually made it safely back to Chiringa after a flight of nearly six hours. The following day it became quite clear that the Japs were on the run. A Beaufighter crew from our squadron took a wrong turn returning from a patrol in the Salween River area and found themselves accidentally flying over Mingaladon, the airfield outside Rangoon. As they beat a hasty retreat they spotted that now-famous message laid out in white bed sheets [sic: whitewash] on the roof of Rangoon Gaol where Allied prisoners of war were being held.

[The first 211 Squadron photograph, dated in the usual marginal markings including the individual pilot’s sortie number, 192. Summarised in the Squadron Form 540 for 1 May, the image is described in more detail in the relevant Oprep 490/Sortie Report No 1 of 1 May (folio 17 of AIR 27/1310), flown by F/O Anthony Montague Browne with F/Sgt Price in Beaufighter ‘L’—serial not recorded. Sortie 192 is his individual sortie reference for the day in that aircraft. The camera, with a 5in focal-length lens (the F5 marking), was of the F.24 series, very reliable and taking 5in x 5in negatives with a useful 250 shot film magazine. This was the 21st image from the magazine. Commonly height and compass heading might be marked also: this shot bears the marking 200 - 50 which may indicate height only. Bearing in mind the 5in focal length (the second shortest as fitted to F.24s and in frequent use by 211 Squadron) the shot certainly seems to be well below 200ft.] Some enterprising RAF prisoners had climbed on to the roof and spelled out the message "JAPS GONE". And to make sure that it was taken seriously and not seen as a trap they spelled out on the other side of the roof "EXTRACT DIGIT" [sic: added later, on another roof]. Anybody who knew about Pilot Officer Prune and the RAF expression "Pull your finger out" could not have been in any doubt about the authenticity of the message! Mont has very kindly sent me a copy of the photo taken by the Beaufighter crew at the time and this is now in my folders dealing with the war years. [Accompanied by 177 Squadron aircraft, the Squadron had sent six Beaufighters to attack in the Rangoon area that afternoon, arriving on target between about 1530 and 1600 hrs. Shortly afterwards, a further three 211 Squadron aircraft mounted further sorties. The Operations Record Book recorded the Gaol sign sighting in laconic terms: “One of these aircraft flew over Rangoon town and saw on the roof of a prison, in large white letters, the words "Japs Gone". The Squadron Sortie Report No 1 of Oprep 490 was a little more forthcoming: “ 'L' F/O Montague Browne F/Sgt Price A number of photographs of the Gaol and its various roof signs were taken by aircraft of 211 and other RAF Squadrons, either during the course of that afternoon, on the next day, 2 May, in the course of numerous sorties reaching the target area from first light and on into the morning, or on 3 May. Sutherland Brown, in his 177 Squadron account Silently Into the Midst of Things, mistakenly reported this particular image (in cropped form and lacking its marginalia, Figure 67) as taken by S/L RH Wood, his CO. Montague Browne also recounted the event in some detail in his Long Sunset: Memoirs of Winston Churchill’s Last Private Secretary, although misrecalling the event as 2 May. Several images of this remarkable sight have been published over the years. It would be interesting to see and compare the various complete prints which lie in the Imperial War Museum and RAF Museum collections, however, the 211/192 “Japs Gone” image shown here and by Montague Browne was plainly taken by him on 1 May. Jim Oblein kept an undated print of the “Extract Digit” image. He was one of those who had been marched from the Gaol by the Japanese on 25 April.] We did our last operational patrol on 5 May 1945 and although we did not know it at the time it was to be our last flight in a Beaufighter—the aircraft that the Japs rather flatteringly called "Whispering Death." [The origins of this well-known sobriquet turn out to be rather more complicated.] It was a standard patrol of roads, rivers and railways and we managed to sink a sixty foot barge and to damage two others. But it seemed to be a somewhat half-hearted effort because it was obvious that there were not many Japs left in our part of Burma. My log book for this last patrol reads "Not much joy—Japs pulling out." It was the end of an era for us and although we didn't know it, it was in fact the end of the war as far as we were concerned. Three days later it was VE. Day and our beer ration was doubled to enable us to celebrate. I think this meant that we got six bottles for that month instead of the usual three! It was about this time that we heard that when the Japs pulled out of the Bassein area the decapitated bodies of two young RAF aircrew were discovered in an air raid trench. They proved to be the bodies of a pilot and navigator from our squadron who had been reported missing during the last few days of operational flying [presumably 187554 F/O Anderson and navigator 187915 F/O Davies, missing from operations 7 May 1945]. Nothing very much happened at Chiringa after that. We seem to have spent our remaining time sunbathing, playing badminton and just lounging around. We did have one disturbing reminder of how grim the monsoon season could be when many of the huts were blown down one night in a severe storm which left the camp flooded.

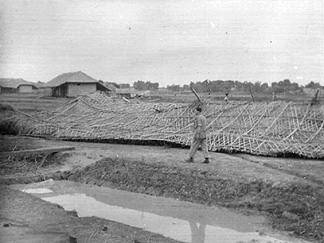

[Variously described as a typhoon or a cyclone, the storm of 14/15 May 1945 destroyed about three-quarters of the Squadron’s bashas - nearly half the domestic camp, the messes remaining undamaged. There were no casualties. The Squadron had been stood down from operations just four days before.]

[In the general conditions, the bamboo and attap bashas were cool enough in their way. And dry enough. Not storm proof!]

[Ron doesn’t mention it, but the Operations Record Book notes that just one man was trapped in the debris and later treated for shock.] We had to hang most of our clothes and bedding out to dry between the rain showers and struggle along as best we could until the huts were re-erected. Fortunately there was always plenty of local labour available for this purpose. There was one advantage of the monsoon. We had no proper bathing facilities at Chiringa and it was customary to bath on the veranda of the hut in a folding canvas bath about three feet square and four inches deep. In the monsoon one just grabbed the soap and went outside for a nice refreshing shower.

Towards the end of May we learned that the squadron was to convert on to Mosquito aircraft and that for this purpose we were to move to Bangalore. And so we left our beloved Beaufighters behind and began the long and tiring journey to Bangalore by road, river steamer and rail. We arrived at Yelahanka airfield early in June and spent a month there carrying out familiarisation flying on the Mosquito followed by low level flying and dive bombing practice. The Mosquito was a much lighter and faster aircraft than the Beaufighter and had one great advantage as far as the navigator was concerned in that he sat in the front cockpit almost side by side with the pilot. On the debit side he didn't have his own gun to keep him occupied and help him feel secure! A couple of tales from Yelahanka. We had only been there a short time when there was a commotion outside our hut and we discovered that the native bearers had found a sleeping cobra behind a pile of bricks and tiles. The RAF went to the rescue armed to the teeth and the cobra was duly despatched. I can't claim to have played much of a part but I was there! The latrines at Yelahanka were primitive—nothing new about that. They consisted of a row of wooden cubicles each with its own bucket with a lid. From time to time they were emptied by the native bearers by means of trapdoors at the back. These trapdoors served a dual purpose, however, and it was not uncommon to lift the lid and come face to face with an enormous rat perched on the edge of the bucket. I could never quite get out of my mind the thought that one day a rat might make its way in while I was actually sitting there! Yelahanka holds very sad memories for me and Mont because we lost two crews within four days. A very old friend of Mont's—Bill Wilkes—was killed with his navigator while flying a fighter affiliation exercise. They crashed on to a native village killing thirty eight people and injuring a further twenty. Four days later the squadron was practising for an air display. I cannot recall the purpose of the display but it involved close formation flying. Somehow Ken Webster, a friend since Cyprus, lost control and crashed. Both he and his navigator Jackie Hopes were killed. [...]

[The exact details of both events are still obscure, being only briefly recorded in available Squadron and RAF records. Losing four comrades in two non-operational accidents so near the end of the war affected the men deeply, then and today. It is not easy to reflect on such events afresh after sixty years. Nor is it easy to report.] After our month at Yelahanka with all its unhappy memories we were glad to move on to Madras for the next part of our training. We were posted to the airfield at St. Thomas's Mount to continue training in dive bombing and low level and formation flying. This seems to have been, in general, quite an enjoyable period for us. I have no record of any serious accidents although to judge by past experience it seems probable that there were some minor ones. My photograph album certainly gives the impression of a fairly relaxed time. The only real drawback was that I somehow developed a rather nasty boil or carbuncle on my back and had to spend some time in the sick bay while it was being treated. This, however, had its lighter side because I was with a cheerful group of blokes one of whom was a bit of an artist. He drew several cartoons based on ideas which I suggested to him and the results can be seen in my folders dealing with the war years. The boil left a rather nasty scar on my back which has been a source of amusement for my grandchildren because I used to tell them it was the result of a bullet wound. I have two other particular memories of Madras. We used to go into the town to one particular cafe where they served iced coffee and cashew nuts. It was the first time that I had had either and I found the coffee very refreshing in view of the temperature and have been addicted to cashew nuts ever since. My other memory is of having been subjected to an attack from the air. We had acquired a dog which belonged collectively to half-a-dozen of us. It was christened Zift—Arabic, I think, for "shit." It was the practice to take it in turns to bring a plate of scraps back from the mess after dinner each night and on this particular occasion it was my turn. I was walking back from the mess carrying a tin plate piled with food and chatting away to Mont when I heard a very loud swishing noise and felt an enormous thud on my arm. I had been dive bombed by a very audacious kite-hawk and Zift's food was scattered far and wide. No real damage done but it gave me quite a shock. No wonder we called them shite-hawks!

During July we began to hear whispers of what might be in store for us. Although the Japanese had pulled back from Burma they were still occupying Siam (now Thailand) and Malaya and Singapore. Rumours were rife that there was to be an invasion of the Malayan coast and Singapore. When the beaches were secured our ground staff would go ashore and either man any captured Jap airstrips or prepare emergency strips in the jungle. We would then fly in the Mosquitoes and take it from there. This all sounded rather hazardous and although it was only a rumour we knew that rumours usually contained some grain of truth and we were not at all keen on the idea. I don't want to belittle the efforts or achievement of the Allied troops who took part in the D-Day invasion of Europe but invading the Malayan coast would have been a different kettle of fish as the Americans knew to their cost from their assaults on the Pacific islands, since the Japs had a reputation for digging themselves in well and fighting fanatically to the last man. Be that as it may, we carried on with our training as July moved into August and then suddenly, without warning, the war was over. The two atomic bombs had been exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese had surrendered. I have no recollection at all of celebrating the end of the war but I feel that it must have been one hell of a party since for the first time in years we were all able to contemplate some sort of future for ourselves. But it was not necessarily a future which was yet just around the corner. Chapter 13: Show Me The Way To Go Home Demobilisation was based on the formula "first in first out" and since there were hundreds of thousands of servicemen who had been in uniform since 1939 ( and in some cases before) it will be quite evident that having been in since only 1942 1 wasn't going anywhere in a hurry. We were all assigned "demob" numbers based on our age and length of service and we simply had to soldier on until our numbers came up. We stayed at St Thomas's Mount until early October and then were given leave. We went up into the Nilgiri Hills to a hill station which in peace time had been the preserve of the privileged whites in India. Officers in the pre-war Colonial Service used to send their wives and families up there in the hot season and it was easy to understand why. Wellington, Coonoor and Ootacamund were 6,000 feet above sea level and how different the temperature was after the Indian plains. The scenery was magnificent and although I cannot remember in detail what we did I know that we had a great time. After all, the war was over! While we were "up at Ooty" as the saying went, we heard that we would soon be going to Siam to become part of the British Occupation Forces there. On our return from leave we flew to Siam via Rangoon where we were fortunate enough to be able to visit the famous Shwe Dagon Pagoda (the Temple of the City of Gold). This was a fabulous experience and one that I shall never forget. Another interesting experience in Rangoon was our visit to the Garrison Theatre to see an ENSA show featuring Tommy Trinder who was a big name comedian in those days. The show had barely started when the power supply failed and the entertainers were left in complete darkness. Tommy Trinder came on stage with a hurricane lamp and gave a faultless performance and I have always had the greatest admiration for him since. A similar thing happened many years afterwards when Pam and I went to see our heroes Morecambe and Wise at a cinema in Sutton. The lights failed and they did a large part of their act by torchlight proving what consummate artists they were. We finally arrived at Bangkok's Don Muang airport at the beginning of December. My Log Book shows that we didn't do a great deal of flying in Siam. Soon after our arrival there was some practice formation flying—I suspect to impress the natives—and on a later occasion Mont and I took a Mossie down to Singapore for repair and came back as passengers in a Dakota. And that was it.

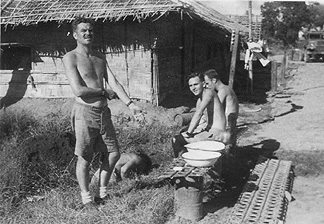

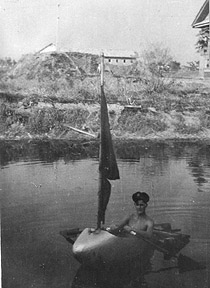

Apart from that we had a pretty free and easy time. We were billeted in wooden huts on the perimeter of the airfield and they were built up on stilts because of the heavy rainfall in the monsoon season. They were quite comfortable although they had one or two unique features. First of all, we shared our accommodation with a number of geckos—brightly coloured lizards about nine inches long. We used to lie in bed and watch them scurrying about on the roof timbers above our heads. We once watched a gecko move its whole family of babies one by one from one part of the roof to another. There was a great deal of activity of this kind and we were thankful to be sleeping under mosquito nets. Another daunting feature of the billets was the toilet situation. We had to come down a wooden staircase to the latrine pits which were at ground level underneath our sleeping quarters. They were literally deep pits in the ground with the usual wooden seat across. If you shone a torch down into the mess below, the whole surface moved. They were inhabited by hundreds of slow-worms which seemed to be carrying out the task of destroying the sewage. It was all a bit disgusting and certainly an incentive not to sit for long with bits of one's bare body hanging over the aperture. We were also fortunate enough to have Jap prisoners of war to clean our billets every day. This was all part of the plan to cause them to lose face and to accept defeat. For the same reason they were required to salute all Allied servicemen regardless of rank whenever they came face to face. I remember on one occasion we went into Bangkok in a lorry and passed several truckloads of Japs. They all had to salute us and we of course had to respond each time. I'm not sure who suffered most! In taking over the airfield we had also taken over large amounts of Japanese stores. As a result of this all the aircrew on the squadron were issued with Japanese flying boots and, as mementoes, Samurai swords. I still have my Samurai sword in the loft (as all my grandchildren know) but the boots are long gone. I wore them quite a lot while at Bangkok and the Jap who looked after our billet used to clean them for me. One day the cheeky little devil indicated by sign language that I should give them to him. I indicated by sign language that he should get stuffed! I can't remember anything about the food or the messing facilities at Don Muang but I do remember that peddlers used to come round selling coconuts. These were not as we see them in the shops today but complete in their green outer skin. We sliced the tops off with parangs or machetes and drank the milk straight from the nut. It was so cool and so refreshing. As I have already indicated we had a pretty free and easy time in Siam. There were some quite large —and quite deep—ponds around the airfield and we used to do a bit of fishing. On one occasion we caught a very ugly fish about two feet long and as there were no inlets or outlets we wondered just how long he had been growing to that size. There were also several streams where we went boating. We had two craft. One was a fairly conventional canoe, rather like a kayak and as far as I can remember it was made of treated canvas. The other was one which we had constructed ourselves from the wing tank of a Mossie. Both were a bit unstable and we suffered a number of duckings.

Monty’s comment: “Ricky sailing in one of the klongs that surrounded Don Muang. Made from an "old" wing drop tank.” Don Muang and Bangkok lie on the flood plain of the Chao Praya, and abound in canals: klongs. Because there was so little to do, Johnnie Sleight—a friend from ACRC days—and I sought permission to set up a library. We begged, borrowed and stole as many books as we could lay hands on and commandeered a room where we could erect shelves. I can't really remember whether it was success or not. I only know that it kept us occupied for a while. In January 1946 we were warned to expect a visit from the Supreme Commander, South East Asia, Lord Louis Mountbatten (having seen a television programme recently about the RAF mutiny which took place in South East Asia about this time I now suspect he came to give us a pep talk to ensure that we didn't join in!). The visit of course gave rise to loads of bullshit as everything had to be just so. One of our jobs was to whitewash all the stones bordering the drive up to the Headquarters building! The day finally arrived and after the great man was escorted from his aircraft he was driven to a large hangar where we were all gathered to receive his words of wisdom. A podium had been erected for him in the centre of the hangar and he ran up the steps to this rather like a boxer entering the ring for a title fight.

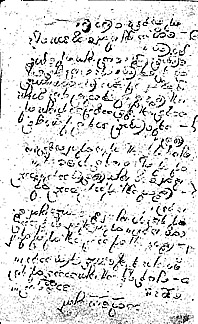

He was wearing an immaculately tailored bush jacket with short sleeves and his arms and face appeared to be bronzed and sun-tanned. We were fairly near the front and it soon became obvious that he was in fact wearing a fair amount of make-up. We were all drawn up in ranks around the podium and he began his talk to us by beckoning with both hands and saying in a very democratic way "OK chaps, break ranks and gather round." I don't remember very much about the speech; I think it was to thank us all for our efforts and, as I have already said, possibly to stop us joining in a mutiny. I was too intrigued by the sun-tan make-up! In February we were once again allowed to go on leave and this time we went to a leave camp called San Sook. It had miles of sandy beach and I expect today it is a thriving tourist resort. In 1946 we had it all to ourselves and I remember long days spent on the beach, in the sea and on native boats. We even built sand castles. I had by now obtained a 35 mm camera to replace the old box Brownie that I had carried halfway round the world and this was the first occasion that I took what I considered to be real photographs. As far as I can remember I "purchased" the camera for eight hundred cigarettes in the local bazaar. I mentioned earlier in this chapter that Mont and I had flown a Mosquito down to Singapore for repair and I see from my log book that this was in February and that it was in fact our last flight together as a crew. We had a week in Singapore before returning as passengers in a Dakota. I suppose we must have seen a fair amount of Singapore during that time but the only thing that I remember with any clarity is our attendance at one of the War Crimes Tribunals at the Singapore Supreme Court. The man on trial was Major General Fuchuei Shempei who had been in charge of one of the infamous camps housing British and other Allied prisoners of war. These camps were notorious for their cruelty and inhuman treatment of prisoners. The trial was a long and tedious affair because each question and answer had to be translated by a Japanese interpreter. The defendant was trying to argue that he didn't know what was going on in the camp that he commanded. The thing I remember most was his answer to the question "What did you feel when you saw that the prisoners were so ill and that they were being ill-treated?" With total composure the Major General replied through the interpreter "I was very sad!" I should perhaps have mentioned before now that life overseas was made bearable by the unceasing flow of letters from home together with generous gifts of cigarettes and tobacco sent out by relatives and friends. The mail was not always as regular as it should have been because we moved around quite a bit and it had to catch us up sometimes out of date order. Pam and I always numbered our letters to each other so that we would at least know if any were missing. We also had a very simple code because all mail was censored before leaving the station and for security reasons we were not supposed to let anybody at home know where we were. As far as I can remember I used the initial letter of every fifth word in the first paragraph to spell out my location. I was thus able to let Pam know where I was as I moved around. All very much against the rules, I'm afraid, although I don't suppose I was the only one doing it. The other thing that we introduced later on was when I was able to form some assessment of when I was likely to be going home. We fixed a probable date and counting back from it headed all our letters DTG (days to go) followed by the number of days remaining. We returned from Singapore to find that arrangements were being made for the squadron to be disbanded. This was more or less to be expected because there was now no role for many of the squadrons and in any event more and more aircrew and ground staff were being demobilised each month. I found myself posted to No. 85 Repair and Salvage Unit which was based at Rangoon and on 18 March I left the squadron taking sad farewells of Monty and all my other friends, some of whom I had been with almost from the beginning. I didn't know as I left Bangkok on my way to Rangoon that I would be returning some forty years later as a tourist. The how and why of it... Though the years advanced and some detail faded, Ron Kemp shared some vivid memories of action and the sillier aspects of Service life with his friend and crewmate Monty Walters. And while names may not be the easiest to keep in the head, many still came to mind as their photos and andecdotes show. Ron remarked to Monty that he recalled Basil Salkeld (Doug Winton’s Nav/W) in particular, while others who came to mind were Alan (Alfie) Wythe DFM, Georgie Price, Ray Wood & his Nav/W Johnny Sleight, and Ron Watling, cousin of Jack Watling the English actor. Meeting Jack in the foyer of The National Theatre London some years ago, Ron made himself known and spoke of his old Squadron, to learn that the Watlings had not only been cousins but best friends—Ron Watling died in 1954. It has been a pleasure and a real privilege to bring together this rattling good narrative thanks to Ron’s interest and kindness, together with a cracking collection of photographs courtesy of Monty, and thereafter with much additional help from two men who once had their hands full in the skies of Burma. Birthday celebrations July 2012 ...and a last farewell There, after some careful re-organising, he had a room with a view, out over the garden. With constant care from close family, he was able to set about getting a bit more mobile again, as well as taking up the odd chat with his old mate Monty, who had also got through a pretty rough period. The two had been friends for seventy years. Ron had reached a great age, with memorable times to the last. After a final wonderful Summer with his family, the end of the long, long road had come, as it must for us all. Ronald C (Ron, Kempie) Kemp died peacefully at home on Friday 22 August 2014 at the age of 92 years. It was a pleasure indeed to have known such a man. He will be much missed by family and friends. Sources RC Kemp Who Could Ask For Anything More Ch 11, 12 (ms 1995-1997) H Besley Pilot—Prisoner—Survivor (Darling Downs Institute Press 1986) www.211squadron.org © D Clark & others 1998—2025 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||