|

|

|||||||

|

W/O James Henry Oblein 1602241 RAFVR Jim (or Jimmy) Oblein was a Warrant Officer and Navigator on 211 Squadron in 1944, during the Beaufighter period of the second Burma campaign. Shot down in September 1944, he and his pilot Flying Officer Shippin were captured and held as PoWs in Rangoon Gaol. Both survived. Oblein and “Shippy” Shippin are listed as casualties on the India and Burma roll. While mis-spelling of names is as common in service records as anywhere else, it is pleasing that an error has now been corrected: Oblein replacing O’Brien. The family name is sufficiently unusual to give rise to frequent mis-spellings.

While recovering from a stroke some years back, Jim found himself mulling over his war-time experiences. His narrative of his RAF service is the result. Jim Oblein died on February 14th 1995 from a heart attack while holidaying in Portugal. John Oblein, who has been gathering information about his father for a family history, came across this website while looking into the Far East campaign. He kindly contacted me and put together a summary of service and a transcript of his Dad’s story. I’ve silently tidied up the Summary a little. The Narrative is verbatim. Summary of service 1942-1944 20 Apr 1942: Joined the RAF, aged 18 and a half.

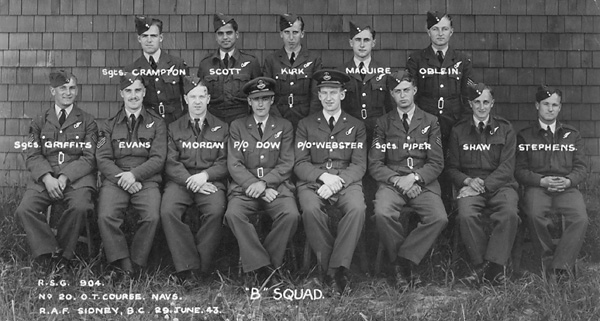

Jim last on the right, rear.

And so to war 12/4 Portreath, Cornwall to Rabat Sale, Morocco in 6hrs 15 minutes. At extreme range for the Beaufighter, some of the formation didn't make it running out of fuel and ditching. June & July 1944: Rocket firing course and cross country flying at Ranchi.

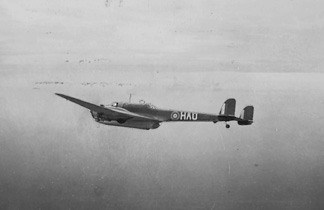

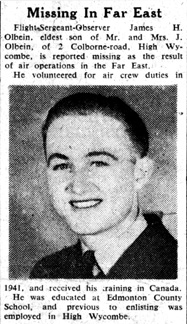

Cutting from the High Wycombe local newspaper, Buckinghamshire Free Press of 20 October 1944. An operational postscript: This recalls events recounted to John by his father, in these terms: "We (flying singly) were looking for coastal shipping and saw several vessels at anchor. I sent their position in anticipation of a rapid attack. When we landed, nothing had happened. We queried this and they said I had omitted to give a direction of travel. I responded that as they were at anchor, there was no direction to be given". The narrative of W/O JH Oblein After completing the Wireless Course, the complete 50 personnel were shipped to Canada. We sailed from Glasgow on the RMS Andes and as it was an independently routed merchant vessel, it changed course every three minutes to avoid U-Boats. The north Atlantic in December was very rough and almost everyone on board was sea sick. We arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia on December 24th and then entrained for Monkton, New Brunswick, arriving on Christmas Day and having a Christmas lunch of streaky bacon and tinned tomatoes. After three weeks we were posted to Hamilton, Ontario for navigation training. I found flying in Avro Ansons in snow storms most disturbing and I was regularly air sick. After four months I qualified as an Observer and was posted to Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island for a Coastal Command General Reconnaissance Course over the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, where the sea was frozen. Completing that course led to a posting to Victoria, Vancouver Island, No.32 Operational Training Unit. On arrival I was quite concerned to find I was going to train on Handley Page Hampden medium bombers that had been converted into torpedo bombers. Within days I found I had a pilot and two Australian Wireless Op/Air Gunners as a future operational crew. It was at Patricia Bay, as this aerodrome outside Victoria was called, that I experienced my first plane crash. We were taking off one afternoon for an exercise over the Pacific when the plane began to swerve to the right, then the undercarriage on the portside collapsed and the port wing fractured by the fuselage and took a vertical position as the plane came to a halt. I was sat behind the pilot for takeoff and I opened the entry hatch above my head to see the port engine above me. My gear was in the nose and I slid down under the plane's seat to collect it. To my disgust the previous navigator had been air sick into the map rack in which I had placed my maps. Just then someone outside was knocking on the perspex nose and yelling at me to come out from the wreckage, but as I was in a foul mood over my maps I swore at the person. I then gathered all my gear and climbed out to find the man who had been knocking was the Station Flight Commander and he immediately gave me a severe reprimand for not leaving the wreckage as soon as it came to rest. He pointed out to me that I would have been in danger had the plane caught fire as there was a large spillage of petrol. After completing the Operational Course we were to be sent back to England. We had to entrain from Vancouver to Halifax for shipment, but on reaching Halifax we were informed that there had been a change and we entrained for New York and boarded the Queen Mary. On reaching Greenock we were informed that Hampdens were now obsolete and we were posted to Crosby on Eden, near Carlisle for conversion to Bristol Beaufighters. Navigators had first to do a six week Wireless Refresher Course at Squires Gate, near Blackpool. Because of the change of aircraft we lost our two Australian Air Gunners. The four month Operational Course was completed without mishap and we picked up a posting to the Far East! Firstly we were posted to a Ferry Training Unit at Melton Mowbray where we were to put a brand new Beaufighter through tests to check fuel consumption etc as we were then going to ferry it to India. During this Course we had another "ground loop" (a swerve on takeoff) but incurred no damage. On completion of the course we were directed to fly to Portreath in Cornwall to prepare for the flight to India On arrival over Portreath we found that the runway in use had to be approached from the sea and began at the top of the cliffs. My pilot made a good approach and was preparing to make a three point landing when we were hit by a strong updraught from the face of the cliffs. The tail of the aircraft hit the runway first and broke off. After a rather scary passage across the airfield towards the Control Tower, the plane came to a halt without hitting anything or anybody. On reporting to the Control Tower we were instructed to return to Melton Mowbray for another aircraft. This we did and completed the tests and then returned to Portreath. The instructions we received for our passage to India were as follows: The flight was uneventful and very enjoyable, although I was asked if I would navigate for three nightfighter Beaus to Cairo as there had been some problems for the nightfighter navigators crossing the Bay of Biscay on the first leg, during which three had run out of fuel and landed in the sea off Portugal. Nobody was lost. My problems started when we arrived at Bahrein, which is only about eighteen inches above sea level and with the heat haze completely obscuring the runway, we dropped onto it from about twenty feet and burst a tyre. We had to wait several days before a replacement arrived and we could continue our flight to Karachi. The heat here was unbearable, I fainted on parade and was taken to Hospital with suspected dysentery. The Medical Staff certainly got that wrong because in the four days I was in hospital I was constipated. On discharge I had to find my own way back to the transit camp, about fifteen miles but fortunately I managed to thumb a lift with an American airman who was stationed on an aerodrome near the transit camp. He dropped me at his base and I had my first sight of a Boeing Superfortress. The next posting was to Ranchi in Bihar State for the pilot to take a course on firing rocket projectiles. No transport was offered and we went to Karachi Airport and managed to get a lift in an American Liberator bomber which was going to Calcutta. Unfortunately they flew at twelve thousand feet and as we were only wearing tropical kit, we found it extremely cold. We had an overnight stop at Allahabad where the temperature on landing was 110 degrees F in the shade! On reaching Dum Dum Airport the next day we managed to persuade the American pilot of the postal plane which was a Lockheed Hudson, to take us on a rather bumpy flight to Ranchi. The one hairy flight there, was an evening exercise for the pilot consisting of "circuits and bumps" (takeoffs and landings). On coming in to land we bounced several times down the runway and the pilot decided to abort the landing and do another circuit. Unfortunately he forgot he had his propellers in fine pitch for landing and needed coarse pitch for takeoff . When he realised that we were not getting airborne he changed to coarse pitch and we just managed to get airborne at the far end of the runway. On completing the course we were posted to 211 Squadron, operating from Chiringa airfield a few miles south of Chittagong. Our first twelve flights were uneventful and prior to the next flight we were on standby in the control tower. One of the crews returned from a trip over Burma and reported that they stopped a train carrying aircraft parts, but had run out of ammunition before they could destroy them. My pilot telephoned Group at Chittagong to report this information and he was left to make the decision as to whether we should take off to find the train and destroy it. He decided to go and we set off on our 13th trip on September 27th 1944 [flying Beaufighter NE762 ‘E’]. We found the stationary train and blasted it off the track with our rocket projectiles. Instead of returning to base, my pilot felt we had only been over Burma for about an hour and asked me if there were any likely targets not too far away. I checked my map and told him we were not too far from a rail head where trains were loaded with barrels of oil but that it had a reputation of being well defended. He decided to investigate and make an attack if there were any targets. I said we would make our attack flying low and when we got within one mile of the target, I would tell him to climb to 1,000 feet before commencing to attack. The name of the target was Chaukpadang and when we climbed we could see several trains loaded with oil. An excellent attack was made using cannons and the trains went up in smoke. My pilot was feeling very pleased with his efforts that he forgot one of the warnings he received on arrival with the squadron, which was never fly low over small hills as there were usually light machine guns sited on them. We came out of the rail head and lifted over a small hill and were hit badly by machine gun fire. One engine had to be feathered and the other engine was not performing too well. We managed to gain a little height and as we started to cross the River Irrawaddy, which was about one mile wide as this was during the Monsoon season, the engine began vibrating and my pilot told me that he was going to have to put the aircraft down. He subsequently made a very good belly landing in the paddy fields near a village called Minbu. We made our way in a westerly direction towards the mountains and I took my parachute to provide some cover if it rained heavily, as it was likely to do in the Monsoon season. We had to use our Kukri knives to hack our way through thick jungle and we stopped to spend the night in the jungle under the cover of the parachute as it had started to rain heavily. The next morning we set off again until we came across a band of Burmese with long knives hunting an animal that had attacked their livestock in their village. We invited them to approach but they refused because we had revolvers. After laying down our weapons and moving a few yards from, them we were approached by one of the party and he was fluent in English. We asked him if he could provide a guide to take us as far as the foothills of the mountains and he agreed. He invited us to his village where we were pleasantly received by the other villagers and they provided us with a breakfast of water and sweetmeats. We then asked if we could bathe at their well and they agreed. We were involved in our ablutions when they brought in Japanese Soldiers. They took us captive and over the next week we were passed from one unit to another. One unit was based in a very nice villa and the captain in charge was very kind to us, providing Kooa cigarettes and sweets. But one afternoon he took us into the garden and positioned us against a wall and then lined up a firing squad. We both thought our time had come and had a few words of departure before the rifles were raised and triggers pulled. This moment was a joke played by the captain who laughed at our discomfort and the rifles weren't loaded. We eventually arrived in Rangoon and were put in a cell in Rangoon Gaol. We soon got used to the daily routine and the food which was boiled rice and vegetable soup, except for breakfast which was like a brown porridge made with rice polishings. The other prisoners told us to eat this porridge called Nuka, as it was the only food containing vitamin B1 which was effective against Beri Beri. The only thing that may have put us off eating Nuka was that it was full of small white grubs. The standing joke was that these weevils were cooked and provided the only meat we were likely to get. We had a firm teak platform to sleep on, and, as I found it difficult to sleep without a pillow I used one of my boots, resting my cheek in the instep. We had a problem over using the toilet which was an old British Army ammunition box, made of wood with a tin lining. Unfortunately urine tended to rust the liner and we eventually had a pool of urine in the centre of the cell. We were allowed to change the box when we emptied it daily but here again most of the boxes had been used before and leaked. After a number of changes we did manage to find a watertight box. The first bit of excitement occurred on November 5th, my 21st Birthday. Rangoon was raided by a Squadron of Boeing B29 Superfortresses, but they suffered heavily at hands of the defending Zeros, and the Gaol had its biggest intake of aircrew prisoners, some 55 flyers. [John believes his father also recalled this raid as carried out by B24 Liberators. The story, teased out by Matt Poole, is a striking one. On 3 November, there was an American B29 operation in which 49 aircraft attacked Mahlwagon railway yards on the eastern side of the city. This was a really big raid, but no B29s were lost. “Seeing” related events like these as a single picture is a quite common feature of the oddities of memory. Jim’s recall is consistent with this view, and broadly consistent with the events as recorded.] After about four months in the cells, the Japs cleared block 8 of Indians, making them join the Indian National Army which was supporting the Japs under a quisling named Chandra Bose. We were transferred to Block 8, which gave us freedom to move about freely and to have conversations among ourselves, which we were not allowed to do in the cells. One incident happened to me in the cells. As the guards passed each cell the prisoners had to bow. I was eating my lunch one day when the guard came to our cell door and I bowed; he yelled at me in Japanese, which I did not understand so I bowed again. He continued to yell, opened the cell door, came in and whacked me over the head with his teak club, which was about three feet long and about two and a half inches in diameter. The cause of this was that I had bowed while my tin of rice was in my hand . After a couple of blows I put the food down and bowed again, he was satisfied with this and left the cell. This was the only beating I suffered whilst a prisoner. The next surprise came in early April 1945 [sic: 25 April] . We were informed that all prisoners who were fit to walk were to be assembled with the intention of marching to Moulmein to board the infamous Burma Railroad and be shipped to Bangkok in Siam. Some 400 British prisoners left Rangoon one morning [afternoon of 25 April] and started to march. We covered about 12 miles a day, some army prisoners pulling and pushing carts carrying a load of Japanese gear. On the fifth day we had Spitfires fly over us and the RAF prisoners felt that the war in northern Burma had taken a turn for the better, as Spitfires had a limited range. After the sixth day we spent the night in a deserted village. I scouted around the village and found a disused well which I felt would provide some shelter if attacked. The next morning we were informed that the guards had deserted us. The carts were unpacked and a sign was made on the outskirts of the village with the clothing, namely "BRITISH PoWS" and a Union Jack. A party of about six army prisoners stood by to attract any friendly aircraft. At about 11 o'clock, four Hurricanes approached, and even after they saw the sign, began to attack the village with cannon fire. I ran to take cover in the disused well but I found that about eight other observant people had got there before me, and I was on top of them at about four inches below ground level. The shelling finished and I ran around the village expecting to find many wounded, but all I found was one casualty who had a shrapnel wound across one thigh. Then I heard the bad news: the Senior British Army Officer, Brigadier General Hobson had been sitting in a hut planning our escape when a 20mm cannon shell hit him in the chest and killed him. The tragedy of his death was that he hadn't seen England for ten years, having previously been in China before being captured in Burma. The decision was made to remove the sign for safety, but then later in the afternoon we were attacked again, this time by American Mustangs. Thankfully no one was injured; I had taken shelter in a paddy field by a dividing wall. Later that evening we were given food by the inhabitants of a nearby village but we had to be kept out of sight as there were Japanese soldiers retreating individually through the village. Then we heard the news that a British Army Officer had persuaded a Burmese boy to guide him to the lines from which we could hear artillery fire. The next morning we were assembled to meet tanks and lorries that had been brought to our position by the British Officer who had succeeded in locating our forces. When we arrived back at the position the army had occupied, many of the prisoners of the West Yorkshire Regiment met up with old friends, as we had been rescued by their own regiment. An apology was made at the evening meal as they were short of food and could only offer us rice and corned beef! You can rest assured that this was gratefully accepted as it was so much better than anything the Japs had given us. We were awoken that night by yells and screams, and when we enquired next morning as to the cause, we were told it was the Ghurka soldiers, who were on guard round the perimeter wire, opening up the wire, letting in Japanese stragglers and then killing them with their knives. The next day American bulldozers arrived to construct a landing strip to allow the RAF transport planes to land and pick up all the rescued troops. I was flown back to Comilla where I was placed in a military hospital, in a ward with other RAF rescued personnel. The next day we observed that there were a number of armed guards between our hut and the next one. When we asked why they were there, we were told that the next hut contained Jap PoWs, and they thought we might make some retributional attacks on them for the way we had been treated. We assured the authorities that their worries were unfounded. My fondest memory of Comilla Hospital was a surprise visit by the Air Officer Commanding the RAF in India, one Air Marshal Coryton. A photograph was taken when he was talking to me and it appeared in a Forces Magazine. I came across this when I had reached Bombay and I sent money to the publishers in Calcutta for two copies, but unfortunately I never received them. We were given the choice of returning by air or sea and I chose air. I flew in a Dakota which landed at Tel Aviv in Palestine for the first stop, and after an overnight break, took off and flew to Sardinia for a short stop before going on to an airfield in Somerset on June 17th 1945. I was part of the first batch of Japanese ex-PoWs to arrive in England. We were entrained to a reception unit at RAF Cosford that had handled a lot of ex German PoWs previously and they had removed most of the home comforts that the unit had been equipped with. Later the first evening in a lounge I was fortunate to pick up a very tatty magazine that turned out to be the one with my photograph. I quickly folded it and put it in my pocket. I took advantage of a rehabilitation course at Ascot which was previously occupied by the American High Command, namely Sunninghill Park, which was going to be the home of Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh when they married; but unfortunately it burned down. I returned to civvy street in April 1946. End piece

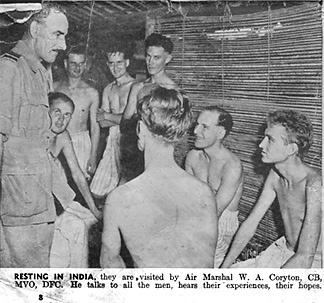

RESTING IN INDIA they are visited by Air Marshal WA Coryton CB MVO DFC. He talks to all the men, hears their experiences, their hopes. It has not been possible, so far, to identify the journal in which the whole Rangoon liberation article “Rescued from the Jap” was published. The photographs are credited to SEAC Photo Unit AAF & RAF. The article may have appeared in Phoenix: South East Asia Command's Picture Weekly and elsewhere, but has proved elusive to date. Air Marshal Coryton is also seen arriving with Mountbatten for the 18 December 1944 inspection of the Squadron at Chiringa, among Cpl Goodinson’s photographs. Sources H Besley Pilot—Prisoner—Survivor (Darling Downs Institute Press 1986) www.211squadron.org © D Clark & others 1998—2025 |

|||||||