|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sergeant George Michael Kendrick 402202 RAAF 1912—1996 From the late 19th and on into the early 20th century, suburban Sydney was spreading around Botany Bay and on to the South. Soon the railway network was expanding to match—in 1884 the new Illawarra line brought stations to Rockdale on the western shore of the Bay and to neighbouring Kogarah, on the George’s River. Both were made municipalities the following year. As the suburban fringe became more established, the young population also grew and by 1909 Kogarah Boys School had opened as a Marist Brothers primary school. A short train ride or a brisk mile or so walk away, at Gibbes Street in Rockdale, English bricklayer Thomas Kendrick and his Australian wife Annie Maud were to make their home and bring up two sons, Thomas Alfred and George Michael (born 30 September 1916).

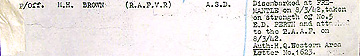

With Air Gunner’s badge having passed out of 1 BAGS, Evans Head in February 1941. In due course, George Kendrick went to Kogarah Boy’s School, known then and later simply as Marist Brothers Kogarah. In 1929 he left, to attend Marist College, Darlinghurst. The High School, on Liverpool St, has been closed a good many years now. In 1930, as the Great Depression bit hard, young George was about to complete his third year of secondary school with the usual Intermediate Certificate examination. At that time, the “Inter” was a very sound level of schooling for every day folk. Then a difficulty arose. For reasons unstated but beyond his control, Kendrick was unable to sit the examination. The shadow and substance of war Although the War must have seemed very far away from Australia in December 1939, Kendrick had already made up his mind what to do. Aged 23, he enrolled in the RAAF Reserve that Summer. A six-foot very active sportsman, he listed his sporting interests: tennis, football, cricket, swimming, golf and basket ball. And somehow, seeing the storm clouds gathering, he had also found the time (and somehow the pennies) to learn to fly—by the end of 1939 he had 16 hours dual and 2 hours solo in his log, all flown at Kingsford-Smith Air School. For active young men, the Phoney War was rather a testing time, as the armed forces of the British Commonwealth set about gearing up to enlist the rush of keen volunteers. That December, the RAAF accepted his application for aircrew and sent him home. The Empire Air Training Scheme may just have been agreed upon, but much remained to be done before flying training could begin en masse. By the end of March 1940, nearly 12,000 men had applied for enlistment as RAAF aircrew but only 4,600 odd had been interviewed—and only about 2,000 selected. Of those, just 184 men had begun flying training. The situation for groundcrew volunteers was hardly much better: 57,000 applied, 7,900 selected, 5,300 enlisted. By early April, they had at least enrolled George Kendrick in the Air Force Reserve—perhaps as a result of his pilot’s training and the nascent plans to use civilian flying instructors. In the sea of volunteers, he may have hoped thus to stand out. But it was June 1940 before the RAAF was properly ready to accept him, enlisting him at 2 Recruiting Centre Woolloomooloo as an Aircraftman Class 2 in the usual terms: “for the duration of the war and a period of 12 months thereafter”. Almost everyone volunteering as aircrew wanted to be a pilot. Passing the medical at the necessary A1B rating (fit for all flying and ground duty) he was immediately mustered as Aircrew. But the RAAF had a surprise in store for George. As he could already fly, their preference was to keep him in Australia, as a flying instructor for other aircrew trainees. He was not the only young fellow, keen for active service overseas, to be faced with this unpalatable choice. The speediest way to get flying in action, they told him, was to volunteer for training as an Air Gunner. This he promptly agreed to, and thus 2 Recruiting Centre Sydney completed his attestation papers. It was 24 June 1940. France had surrendered to Germany at Compiègne just two days before. Older brother Thomas Alfred, born 23 September 1915, chose to join the Army. Enlisting in the AMF on 8 August 1940 and called up in October 1941, Private TA Kendrick N24844 served in Australia until his discharge in November 1944. To be an Air Gunner That Winter it was off by train to Victoria and 1 Wireless Air Gunners School Ballarat, on No 3 Course for wireless operators. John Keeping was to be another 1 WAGS trainee.

A serious moment in full flying gear. Sunny scenery, truck, lush grass and a tin shed. Although shed, grass and distant trees seem to have more of an Australian air, family recall has this placed in North Africa, so possibly Nakuru, Kenya. Like others of his youth and spirit, as the course at Ballarat drew to an end that Christmas, George Kendrick cut loose for a little. It must have been a good Christmas Party, as he was absent 3 days 5 hours 10 minutes. On returning to camp at lunch-time on Sunday 29 December to face the music, the CO gave him 10 days in barracks and docked him 4 days pay. It was his first and last brush with Service discipline. In the end, it hardly mattered. Course complete, he was off to 1 Bombing and Air Gunnery School, at Evans Head in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales, where an existing ELG had been developed as the 1 BAGS aerodrome by August 1940. In mid January 1941 he began No 3 Bombing and Gunnery Course with ground instruction and air gunnery in Fairey Battles, not long since retired from operational use in the UK. Typical of the period, 3 Course took barely four weeks for Kendrick to complete and pass, on 10 February 1941. He remustered immediately as a Sergeant Wireless Operator Air Gunner: a WOp/AG to some, a WAG to others.

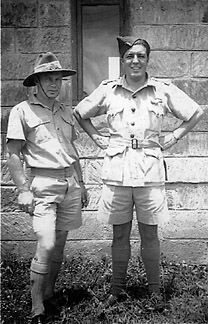

Apparently unrelated, 402202 Sgt George Michael Kendrick (right) and 402201 Sgt Alfred Henry Kendrick (left) joined the RAAF on the same day at 2 RC, passing together through 2 ITS, 1 WAGS and 1 BAGS, qualifying on the same day as WOp/AG, and promoted Sergeant that day. Together they embarked for the Middle East and on to 211 Squadron. In the original photograph both men’s Sergeants stripes are visible. Only George has his winged AG badge up. These details, with tropical kit, Alfred’s Aussie slouch hat, the sandstone building, and the generally pleased air, give a sense that this may be in Sydney soon after qualifying as Gunners at 1 BAGS. By Sea to Egypt Anchored off Bradley’s Head in Sydney Harbour from late February, the fast luxury liner Queen Elizabeth was being converted to a 5,500 berth troopship by the men of Cockatoo Island Dockyard & Engineering. Made ready by early April, she took a brief diversion to Hobart to allow Harbour room for Queen Mary, the other great Cunarder. Fresh from a refit in dry-dock at Singapore, by 1 April she too was in Sydney, ready to embark troops. On the morning of Wednesday 9 April 1941, the two Cunard ships made a stirring sight as they passed each other at Sydney Heads, Queen Mary outward bound for Jervis Bay to await her convoy companions, and Queen Elizabeth returning to embark her complement of troops. Boarding completed the next day and at 7:00 am on Good Friday 11 April 1941, followed by Ile de France, Mauretania, and Nieuw Amsterdam, the Queen Elizabeth made her way back down the harbour towards the Heads. Among the RAAF men aboard her were George Kendrick and Alf Kendrick.

Off Jervis Bay, with HMAS Australia joining as escort, the five vessels took up their convoy stations and set sail for Fremantle and the Indian Ocean crossing to Trincomalee in Ceylon. Far away in Greece that Easter, the war situation was grave. At Paramythia, 211 Squadron was about to suffer loss in action of the heaviest.

From Ceylon, the two Queens set course for Egypt and Port Tewfik, escorted by HMAS Canberra. As in Sydney, Fremantle, and Trincomalee, the Suez Canal port could not take both vessels alongside at once. To add to the difficulties, convoy WS 7 from Britain was also about to make port. It was 5 May before the Queen Elizabeth was able to berth and disembark the RAAF men aboard. They then faced a long truck journey through the night, North to the Nile Delta. In the pre-dawn light, they arrived at Middle East Pool, Aboukir (since better known as Abu Kir, on the Bay of Naval fame known for Nelson’s surprise of the French fleet). About 10 miles away to the West lay Alexandria, the resort town and ancient port.

What they saw: the resort sea front of Alexandria East Harbour.

What they got: the sandy tent-lines at what is most likely Middle East Pool. George, left, Alf Kendrick, centre. Leo, on the right, is a name not otherwise known among 211 Squadron aircrew. The three are pictured among the tents. The hand-lettered sign held by George and Leo says simply “Suez Side”, which may be an elaborate pun on a popular aircrew saying of the day. Or it may be wry reflection on the to and fro of Service life: MEP, the transit camp for arriving and departing airmen, moved from Aboukir on the Delta coast to Kasfareet on the Canal shortly after they landed in Egypt.

They were a month under canvas, with plenty of time for sightseeing in Alexandria and Cairo. A-training we will go... George’s later recall was that he and his crew already had operational experience, possibly with that first brief 211 Squadron stint. Individual service records, like all war-time sources, are not impeccable reflections of the exact course of events. As other RAAF men in the Middle East found, between May and July 1941 there was a rather confused period of postings, some direct to operational squadrons, only to be sent back to an OTU even after seeing action. While the 211 Squadron air echelon had returned from Palestine to lodge briefly at Heliopolis during June, the groundcrew had left Aquir by sea direct for Port Sudan on the 4th and by the 14th were setting up camp at Wadi Gazouza in the Red Sea Hills. The advance and main air parties soon set off from Helio, reaching the scrubby valley between 16 and 22 June. The next few weeks were rather testing. The few aircraft on hand were in a poor state, and there were deficiencies in signalling and other basic equipment. On the 22nd, a storm damaged the Sergeants quarters and other buildings. It was the first week of July before any flying training could start. Around this time, a Blenheim Operations Course of 40 flying hours and ground instruction might last 6 to 8 weeks for each three-man crew. Perhaps it was these difficulties that brought about the next posting for George Kendrick: back to Middle East Pool from 8 July. While the Operations Record Book for this period reflects the difficulties being tackled, there is no mention in the Squadron account, or the later 72 OTU history, of returning trainee airmen to Pool. However it may have been, the next entries in George’s record suggest that he spent some time in Egypt, then an undated move to Kenya Pool, Gil Gil, with attachment to 70 OTU Nakuru at last in late September. Alf Kendrick’s moves mirror this period, with minor variations. It is unsurprising then, that George’s photograph collection shows a considerable interest in sightseeing, not only around Cairo but in Palestine too.

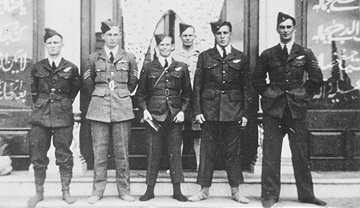

All shoe-less outside a mosque in Cairo, a group of 6 airmen. The Sgt Pilot second from the left is apparently RAFVR, the others are all WOp/AGs in the darker blue RAAF tunic. The shot is apparently from a copy negative, by its soft density. Left to right: Sgt Tom Wixted (404225 Thomas Joseph Wixted RAAF, who shared a tent with George in Egypt, was later lost on operations with 11 Squadron over Burma on 5 April 1943); Sgt Huff (RAFVR) [possibly Sgt HH Hough of 84 Sqn]; Unknown Sgt WOp/AG, RAAF; Sgt AH Kendrick RAAF (rear); Sgt GM Kendrick RAAF, Sgt George UIm RAAF (clearly in RAAF blue, but no current trace in Australian archival records). It was well after the war that George identified all the men in this shot, his wife Olive writing their names on the rear of the print.

Christ visited this place and cured a cripple (Kendrick collection)

From the number and variety of local photographs of well-known Biblical sites in his small collection, it seems that George, a good Catholic lad, spent some time sight-seeing in Palestine. In 1941 there was a fair contingent of Australians there, one way and another, the various Forces papers advertising accommodation both for officers and for other ranks on leave. Accounts of the desert road trip to Palestine (like Tommy Wisdom in Wings Over Olympus, for example, or Olivia Manning in The Levant Trilogy) show that travel on leave from Egypt, though not quite a snack, was certainly practical—whether by Service transport or with mates. This print of the little town of Bethlehem is clearly taken from a moving vehicle—a possible hint that it is one of George’s own. A number of others, of the Church of the Nativity, of Bethlehem and of Jerusalem, are plainly commercial photographic prints. While some carry an identifying number discreetly worked into the actual print area, others carry the maker’s own stamp on the rear: Palphot. Founded in 1934, the firm was then a small family postcard business based in Hertsliya, a newish town on the coast a short distance North of Tel Aviv. Today, Palphot is a major Israeli publishing and souvenir concern still based in prosperous Herzliya, still making postcards and owned by the children of the founders. The firm has a neat commercial website at www.palphot.com. To Kenya and Nakuru

A sunny grass field, tropical uniforms, and four Bristol Bombays making ready to provide transport. The shot does not reveal any aircraft serials, but the nearest aircraft carries the name Athlone below the cockpit, while the nearest of the far flight of three carries the individual aircraft letter E—and is also apparently named, as are the others. No Squadron codes are to be seen but, at this period, certainly aircraft of 216 Squadron, who had helped 211 Squadron with other Middle East movements.

Both of these wonderfully evocative shots are clearly of the same occasion, with closely matching details of light, on-field equipment, and background topography. Only two Bombays are in shot here, the nearest carrying letter J, both with individual but illegible names. The airfield office, centre background, with the civilian vehicles and the same bowser (a Thompson Bros self-propelled re-fuelling unit developed for flying training schools), together offer tantalising hints. Despite the fine shots and equally fine scans, there is a limit to photographic resolution and any sign-lettering details are lost in the emulsion grain. In the absence of more comments or a date, the place is a little hard to determine, though the grassy field is unlike any RAF Station in Egypt. Possibly September 1941, in transit to Gil Gil or Nakuru in Kenya, that “green and pleasant land” that so appealed to Alan Conrad. Kenya had a thriving civil aviation sector in the years before the war. But it might just perhaps be part of the move South, off operations, from Palestine to The Sudan in June 1941. At Nakuru, George was teamed up with an Australian pilot (who he did not name when later recalling his service) and seemingly, as Observer, 407273 F/O Thomas Taylor McInerney RAAF, a 32-year old Adelaide barrister originally from Melbourne. Whether they had crewed up at 70 OTU in the customary apparently casual fashion, or had already got together on first acquaintance with 211 Squadron, is not certain. Despite the relative safety of Nakuru, the sharp edge of war could still touch them. Their unnamed Australian pilot was killed in Kenya. In the records of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia, there is just one RAAF pilot fatality at 70 OTU during George’s training. On 16 October 1941, 406267 Sgt Allan G Shea, a West Australian, was killed in a flying accident to Blenheim IV V5693, while flying solo on a formation practice flight. With one engine out, the aircraft lost height, then hit a tree while attempting a forced landing. It was destroyed by fire. Shea lies with other training casualties of 70 OTU and some World War I men, in the Commonwealth War Graves section of Nakuru North Cemetery, on the road to Kampala. George later remarked that his next pilot “was an Englishman who had lost his crew. We had lost our pilot, so we crewed up together.” From the other Australians accounts of Nakuru, of Helwan and of Sumatra and Java operations, George’s regular crewmates were his pilot, the Scot 44807 F/O Donald Richardson Chalmers RAF, with F/O Tom McInerney RAAF as Observer. Don Chalmers, originally serving as a 2nd Lt in the Cameronians, had volunteered for the RAF in late 1940. Granted a temporary commission on 2 November that year, as the 70 OTU course drew to a close in late 1941 he was made Flying Officer. Over this period and with this mixed crew, Sgt Kendrick would in all likelihood also have met the Australian officer trainees at 70 OTU—Cuttiford, Oddie, Mackay, Payne and others—though the divide between the Officers and Sergeants messes would have constrained them all. Sgt John Keeping the RAAF WOp/AG, who arrived at Nakuru the day after George, met up with his pilot P/O Bev West and observer P/O George Ritchie at 70 OTU, as did Neville Oddie and his crewmates. In the 1980s, George was to correspond with J McCarthy, who was then writing A Last Call to Empire about the EATS aircrew scheme. Recording his training and operational experience by pro forma letter after the passage of some 40 years, George wrote in positive terms on his EATS training and on serving with RAF and RAAF men in an RAF Squadron. He went on to remark with some emphasis that mixing officers and NCOs in aircrews was neither fair nor satisfactory. The separation of crews, tight-knit on operations in the air but parted by the twin gulfs of rank and mess once safely back on the ground, was still sharp in his mind. Despite their setback over crewing, after the usual period to complete the Blenheim Operations Course Kendrick was posted out on 26 November, heading back to the dust and flies of MEP once more. But not for long. To Helwan and 211 Squadron Back in Egypt with 211 Squadron, the strictures of rank and separate Messes could be partly mitigated by resorting to the tent-lines, where easy-chairs and cheek among the sand and flies made for some thing like a beach-side jaunt back home. There the crews could gather and share a joke, even in crisp uniform, as John Keeping’s photographs showed.

A mixed group in the tent-lines at Helwan. Sgt Keeping, the RAAF gunner, at left, looking very fresh. Next to him, equally crisp, his RAAF pilot, P/O Bev West. The other insouciantly shirtless pair are F/O Don Chalmers RAF with book (George’s pilot) and on the right, hatted and wearing sunnies, Bill Wicke or Wickes, a South Australian mate of John Keeping’s. Curiously, the ex-Cameronians Chalmers was simply “a Pommy” to Keeping and “an Englishman” to George—only ”Ginge” Brown had him to rights, as “a Scot RAF chap” (letter to the Oddie family). Within a couple of weeks, Alf Kendrick was posted in as well. On 17 January 1942, both men’s postings record was amended, from 211 Squadron ME to 211 Squadron FE. The Squadron was about to deploy to the Far East for operations against the Japanese. The date recorded is notable, coming the day after the 211 Squadron Sea Party (the main body of groundcrew and their equipment, plus some number of spare aircrew) had boarded HMT Yoma at Port Tewfiq. It was 25 January before the Air Party of 24 aircraft and their three-man crews began to depart Egypt. Setting off as four flights of six aircraft over four days, they took as passengers just a handful of essential groundcrew and their tools, in the most spartan of air-travel conditions. To Sumatra From that outpost, cut from the jungle on the edge of the vast swamps of the Moesi floodplain, they set about their task with whatever was available. The difficulties of the period are covered in more detail on the pages for the Far East, Sumatra and Java and the Blenheim IV. Essentially, in the press of war, the Air Echelon of the Squadron once more faced operations from an exposed if secret forward position, with little ground support (and this time all but none of their own). Mounting sorties with some intensity and in poor weather towards the end of the North-West monsoon season, the Squadron was taking losses in action while struggling for serviceability on the ground. The second week of February drew on. With the vast majority of the groundcrew and equipment still at sea, the first reports of the Japanese landing force approaching Banka Island off the mouth of the Moesi were coming to hand. For the RAF in Java, the tempo of air operations over the next few days rose markedly, to find, assess, and attack the threat. The efforts of the Blenheim Squadrons at P2 to support these efforts were to prove bitter indeed. Problems with the flare-path on the night of the first attack, 11 February, cost three aircraft and the death of four men: Clutterbuck and Newstead of 211 Squadron and Hyatt and Mutton of 84 Squadron. Accounts of the action on 13 February differ, according to the perspective of the source. Some reports and records made after the event recall the 211 Squadron sortie that day as convoy escort duty. True, there had been one earlier convoy escort task, of dubious worth, on 7 February. The nature of such impromptu duty (with its requirement to make contact and loiter) had been sensibly met by two flights of three aircraft, the second dispatched later to relieve the first, and thereby extend the escort period. But the task cost the Squadron all three Blenheims of one wave. Sgts G Steele, S Menzies and G Gornall in Z7586, and Sgts AT Bott, N Lynas and H Lamond in Z9713 were shot down over the Java Sea, none surviving. All were RAAF men. The third Blenheim, Z9659, was also attacked and crashed near P2 on return, with the loss of the experienced F/Lt K Linton who died the next day (his Sgt Observer Offord and Sgt WOp/AG Crowe both surviving). In contrast, on the afternoon of 13 February, at 15:40hrs 211 Squadron CO W/Cdr RN Bateson led six of his aircraft off on a sortie. The records of the aircrew who took part include Sgt John Burrage’s diary, F/O Reg Cuttiford’s Pilot’s Log Book, Bateson’s own Log Book and later report, the Log Book of Bateson’s gunner, Sgt Bill Baird, P/O RF “Ginge” Brown’s letter and report made soon after that, Sgt Penry’s report, LAC Livesey’s diary entry, and George’s own 1980s account. If differing in some details, all agree on the task that afternoon: a low level daylight offensive sweep to seek out and strike the Japanese invasion force. They were unsuccessful. Calendar, season and weather were all against them. That afternoon, the formation was due to return to P2 around 18:00 to 18:30hrs, with sunset at 18:21hrs and no moon. The weather closed in, frustrating their search. On returning, the aircraft reached P2 in a monsoon storm and with darkness gathering. They were unable to sight the landing ground or flare-path. The exact course of events is not completely clear after that, however, led by their experienced CO Bateson, four of the six aircraft were able to grope their way back to Palembang P1, 34 miles to the NW. There they found the flare path lit up and after 4:00hrs or more in the air, the last hour in darkness, all four landed safely at around 19:40hrs. But two aircraft failed to return to either P2 or P1 that night: that of F/O GG Mackay with F/O Oddie (Observer) and F/O J Payne (WOp/AG), all RAAF; and that of P/O Don Chalmers RAF with P/O Tom McInerney RAAF (Observer) and Sgt George Kendrick RAAF (WOp/AG). Those in peril on the sea... At 19:50hrs, Chalmers put their Blenheim down in the Java Sea. It was 90 minutes after sunset, on a moonless tropical night. The aircraft struck the water hard and almost nose-first. Kendrick was first out. A Blenheim gunner had a fair chance of crash survival in the rear cabin, aft of the main spar, provided he had vacated the turret in time. Soon Chalmers joined him in the water. The extended nose of the Mark IV had been designed to help navigators, but it may have been McInerney’s undoing. Don Chalmers neither saw nor heard his Observer again after the impact of ditching. Soon the aircraft sank. McInerney did not re-appear and was never seen again. At about the same time, the pilot of the other missing aircraft was also attempting a forced-landing. Although over land and nearer to safety, luck was not with Mackay, Oddie and Payne that night. It was 25 years before they were found, in the wreckage of their Blenheim, lost in the jungle swamps by the Moesi River some 15 miles from P2 airfield. Back in the Java Sea, the surviving pair were in some difficulty: in the crash, Chalmers had been temporarily blinded and Kendrick badly injured in the leg. Somehow they prepared themselves for a night at sea. Again, the existing accounts are at odds. George much later recalled spending 14 hours in the Java Sea without his Mae West, while according to Brown, Chalmers and Kendrick both had them. Whether swimming, in Mae Wests or in a dinghy, it would have been a very grim night in the water for Chalmers and Kendrick. Towards dawn they reached a small island of the Nangka Group in Banka Strait.

The Nangka Islands group far into Banka Strait, enlarged from the British Admiralty chart in the National Library of Australia (MAP G5741.P5), showing the light on West Nangka. Aboard White Swan in Banka Strait

Originally built in Brisbane by Norman Wright for John McGinnis Williams in 1926 as Francois. A luxurious 70ft auxilliary diesel schooner of 61 tons, Mac Williams later sold her to Merton Brown, who renamed her White Swan and had her sailed to Singapore. This image is a little deceptive about her rig, which was in fact typically schooner, with mainmast markedly taller than foremast. By December 1941 Brown had been manager of Thornycroft Singapore for 16 years. As the Japanese advanced down the Malaya Peninsula, he stepped forward to do his bit once more. Putting his advancing years aside, he volunteered for the RAFVR and was commissioned into the Admin & Special Duties Branch (non-flying, in other words) as Acting Pilot Officer on Christmas Eve 1941. As the evacuation of Singapore got underway, Brown found a way to contribute that brought his maritime experience, his schooner and his RAF role together. In the late afternoon of 10 February, in company with other small RAF, RN and other vesssels including the RN tender Rompin and the private yacht Carimon, he set sail in White Swan for Batavia, with evacuees aboard. In waters by then already very dangerous, the little convoy first made its way to Sumatra. In the late afternoon of 13 February, they reached Muntok, on Banka Island at the Western mouth of Banka Strait, departing in the dusk that evening. By then they had picked up passengers from HMS Siang Wo, an evacuee ship damaged by air attack, and had parted company with Rompin after her engine-room was accidentally damaged by an explosion. Although accounts of the route taken differ, it appears highly likely that they were using the Admiralty chart and the Eastern Archipelago Pilot Vol IV, which gives an extended description of Banka Strait and of the Nangka group, its light, islands, and reefs. The sailing directions for the Strait suggest keeping to the Banka Is or Eastern side, to avoid the shifting mudflats of the Sumatra shore. By the early morning of 14 February they were deep in the waters of the Strait, well beyond the mouth of the Moesi River. Again, accounts differ in detail but by perhaps 08:00 they were close upon Nangka Light, set high on West Nangka, one of the island group about half-way down the Eastern side of Banka Strait and some 80 miles ENE of Palembang. Ashore, on one of the other small islands of the group, they saw a man waving and shouting. It was Chalmers. It must have been a wonderful moment. Soon Chalmers and the injured Kendrick were picked up by one of the boats and taken aboard White Swan. After a fast passage direct across Sunda Strait, she arrived safe at Tanjong Priok in the dusk of 15 February. Ashore in Batavia, the two airmen were able to regain contact with 211 Squadron. Chalmers was to remain with them to the end. He was with the 211 Squadron party that, having journeyed across Java, were among the last to leave Tjilatjap. On 2 March they boarded Tung Song for Fremantle, arriving on 13 March. The injured Kendrick was apparently evacuated separately, although no details of his voyage are to hand at present. He disembarked in Australia on 28 March 1942 at Sydney and was taken on strength at 2 Embarkation Depot. The luck of their being picked up was no less than the luck of their safe return to Australia. An appalling amount of naval and merchant shipping was sunk by enemy action in the waters off Sumatra and Java in February and March 1942. Back at Tanjong Priok, Merton Brown handed White Swan over to Lt Upton RNVR of the auxiliary HMS Rahman. Upton and others took Rahman and White Swan to sea but, intercepted by Japanese naval units, Rahman was sunk. On about 1 March or 2 March, already crowded with survivors, White Swan picked up another Blenheim crew: the Australian F/O Brian Fihelly 404239, F/Sgt T Gomme 751816 and Sgt Eric Oliver 980459, of 84 Squadron at Kalidjati. They had been shot down on 25 February, on a raid to Palembang. Attempting to slip away South and West to Australia, White Swan was intercepted again on 2 March and ordered to return to Banten Bay once more. There they left her, taken into captivity on 3 March. Fihelly, Gomme and Oliver all survived, and their tale is recounted in rich detail in Don Neate’s Scorpions Sting.

Merton Brown, meanwhile, had made his way across Java to Tjilatjap. There he was able to board the RAN corvette HMAS Bendigo. She sailed at 23:30hrs on 1 March, bound for Western Australia. Berthed safely at Fremantle, on 8 March P/O MH Brown disembarked to be taken on strength at 5 Embarkation Depot and attached to the RAAF. It had been a heady adventure. Perhaps he had done enough in two World Wars. Perhaps he was no longer well or possibly his birthdate may have caught up with him at RAF Central Records: he turned 50 in 1942. Whichever it was, with effect from 19 April 1942, Merton Holland Brown resigned his RAFVR commission (London Gazette 16 June 1942 Issue 35598). Returning to Malaysia after the war, he passed away about 1946. Of the pretty schooner once Francois, there remains no certain trace beyond her entry in Lloyd’s War Losses: “Captured vessels March 1942 Generally, a vessel treated as a war-time loss but later returned to or recovered by owners after the war is so noted in the Lloyd’s record. But of White Swan, there is only the brief entry for her capture without further remark. Thus she, too, passed from view. The ravelled sleeve of care At some point after his return to Australia, George wrote an account of their night in the water, which was published in The Catholic Weekly. Now lost, a copy may yet come to hand, to offer more insight into the events of that night beyond his 1945 letter to the RAAF and his 1980s pro-forma reply to McCarthy’s EATS questionnaire. By and large I have preferred reports closest to the events, and those that appear to offer independent corroboration. I have not attempted to reconcile nor to list every variation. The story is vivid enough as it stands: Don Chalmers and George Kendrick were very lucky men. Duty carried out By 1943 he was working in ATC at Amberley in Queensland. There came reward of a different kind: he met Olive Hall, his wife to be. Olive was then the Queensland Commandant of the Women’s Air Training Corps, which had formed in Brisbane in April 1939 as a voluntary service for women interested in being trained for work in the Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force. In July 1945 as the war drew towards its end, George’s final duty to 211 Squadron came to hand. In his years in the RAAF and RAF with Alf Kendrick, their names and service numbers must have caused comment, amusement, and sometimes confusion too. Not for nothing did they mark the odd photo as The Brothers. That month, RAAF Casualty Section wrote first to Alf, by then also in civvies at Abbotsford, seeking information about the loss of poor McInerney. Alf passed the enquiry quickly on to George, through the Civil Aviation Department at Archerfield in Brisbane. As speedily, George set down a long-hand account of the ditching that night back in February 1942. P/O TT McInerney, he concluded, “had no possible chance of survival”. McInerney is commemorated on the Northern Territory Memorial by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. All her paths are peace... A workmate during George’s long career in Civil Aviation was to become a life-long friend. Elwood Herbert “Slim” Summerville was another ex-serviceman, who had stepped forward for the Australian Army when war broke out. In early 1942 Slim Summerville was serving with 61 Battalion, the Queensland Cameron Highlanders, at that time deployed in defensive positions at Caloundra in Queensland. Important but perhaps rather dull duty. At that time, possible invasion by the Japanese was a very serious concern. By late March 1942, Darwin had been bombed half-a-dozen times and evacuated of civilians. Summerville’s thoughts turned to more active service. On 28 March he was discharged from the Army, in order to enlist in the RAAF that day in Brisbane. On the very same day, down in Sydney, George Kendrick arrived at 2 Embarkation Depot, back from his adventures in Sumatra and Java. Summerville was to serve in the RAAF until 1945, marching out from 1 OTU East Sale in November. Finis coronat opus Living in retirement not far away, Slim Summerville came to be interested in knowing more of his late mate George’s war-time adventures. Meanwhile, in Far North Queensland, Julie Dodds (née Williams) was looking into the fate of the pretty little schooner White Swan, named Francois by her first owner, Julie’s late father. Summerville’s son Randell found he was able to assist his Dad, with a collection of his own historical research, with information from Julie Dodds and, having found this website, some of the 211 Squadron story. So these threads all came together, to make an account of the RAF service of George Kendrick as a young Australian airman. Sadly, Elwood Herbert “Slim” Summerville passed away, aged 91, on Christmas Eve 2008 as this page for his old mate George was still being compiled. Still, thanks to the interest of all the families involved, it has been possible to weave these threads into the fabric of the 211 Squadron history and, in passing, salute the steadfast service of two young men in war and their enduring friendship in peace. Thus does the end crown the work: finis coronat opus. Sources Admiralty Chart 3471 Straat Banka 1942 NLA G5741.P5 www.211squadron.org © D Clark & others 1998—2025 |

||||||||||||||||||||