|

|

||||||||||||

|

LAC LW “Abbie” Abbs 615342 RAF 20 May 1920—28 March 2014 Introduction

At the age of 18, Len was already working in photography when he joined the RAF in July 1938. He went on to train in RAF photographic work at Farnborough before being posted to 9 Squadron (Vickers Wellington bombers). He was then posted to 211 Squadron, joining them at El Dabaa on 12 March 1940 at that uncertain stage of World War II known as the Phoney War, before even the Battle of France had begun. One of the originals posted with 211 Squadron to the Far East, there he was taken captive along with over 300 other groundcrew members of the Squadron, at the fall of Java in March 1942. Born in Norfolk at Norwich, Len lived at Lowestoft in Suffolk for many years, an East Anglian through and through. Repatriated from the Far East, Len met Betty Robertson in 1947. Engaged that August, they married on 27 December 1947 and faced the triumphs and hurdles of life happily together down the years, with a growing family of five children, all daughters.

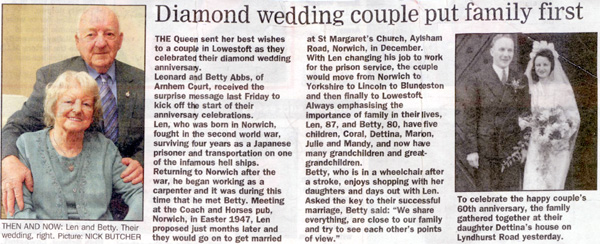

In December 2007 Len and Betty celebrated their Diamond Wedding anniversary, with family in Lowestoft and a message of congratulations from HM the Queen for good measure. Len took care to share the good news, slipping cuttings from the local newspaper in the post to friends around the world. Letters from Len A brief note on style: in deference to Len’s own remarks, I have silently tidied up his spelling and have omitted personal asides unrelated to his narrative, shown as [...]. Any amplifications are shown [thus]. I've made no other alterations: Len's tale is his own and a fine narrative of one man's part in a great tragedy, to be honoured of itself. Pray, read and contemplate but cavil not at his expression nor at his feelings regarding his captors. Letter 8—4—2001 (Middle East) [...] When 211 were at El Dabaa, the British High Command permitted the Palestinians, Jews and Arabs, to enlist and serve with the ME Forces. We had some thirty join our Squadron. I do believe the Powers That Be thought the two factions would unite to serve the common cause. Wishful thinking, for in the mess at meal times Jews would sit one side of the building and Arabs the other. El Dabaa was situated on a cliff-top where there were built sand-bagged machine-gun posts. On the outer perimeter were Egyptian heavy Ack Ack positions who incidentally were a bloody nuisance for at times they fired on our returning planes. Luckily their accuracy was never good. Manning our machine gun posts were the Palestinians. In charge of them was Swede Revit. I got to chat with Swedie because of his accent. On our first meet I said “I bet you come from Norfolk, Bor!” I was wrong, he came from Suffolk: near enough, another friendship was born. Coming from East Anglia we were known as Swedes or Turnips.

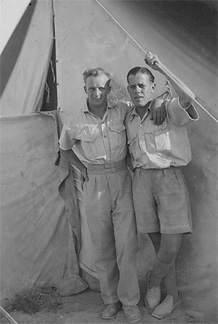

The dust of the desert on their boots as they stand by their tent for a snap. One of the favourite spots for inforrmal shots with mates. The war never commenced in the Middle East until June 10th 1940. I started my service there in March when things were quiet. The evenings there were beautiful. I find it hard to explain, there was a stillness, a hush. So hard to believe that at the time I speak of, Gerry was knocking hell out of London. We would sit on top of the sandbags and chat, one to the other. There I met Isaac [Baruch] who was born in Jerusalem. He spoke 5 languages and fascinated me. He also enlightened me of the situation in Palestine, Jew v Arab, with the good old British Tommy in the middle. [...] Palestine under the League of Nations terms was a British Protectorate. One evening Isaac told me he had got 14 days leave and was going home. He said “Come with me, Abbie”. I said how I would love to but I can’t see the CO granting me leave. Surprise, surprise I did get leave and I travelled with Isaac, 36 hour train journey to Palestine. Isaac’s father was a Rabbi originally from Russia, his wife from Spain. Their eldest son was Aaron, who was imprisoned by the British Army for breaking the curfew and carrying a firearm. This long after I stayed with them and he was released when they gained their independence. Aaron was married to Rachael, they had a baby girl. Also there they [the parents] had four girls, 16, 14, 13, 9 [years] of age. We left the train at Tel Aviv and caught a coach to Jerusalem. Waiting for us at Jerusalem was Isaac’s brother Aaron and one of his younger sisters. After our welcome the girl ran on ahead. Arriving at the house, the Baruch family were lined up to meet us. In a line Mum, Dad and children, also Aaron’s wife Rachael with baby. I thought how beautiful the girls were. I was 19 years of age and was embarrassed by their greeting. Isaac’s father in perfect English said “Welcome to our home, Abbie, we intend to make your stay a happy one”. Boy was it a happy one I looked back [on] over the years. I treasure the memory not only of the pleasure but also of what they taught me. [...] When Isaac introduced me they thought he said “Happy” so to them I was always “Happy”. It was so appropriate [...] The house they lived in was [on] top of a hill, five bedrooms on the ground floor which was much cooler for sleeping. We spent the time upstairs when we were not visiting the sights, we played cards, danced to tunes on the gramophone. I flatter myself I was in great demand. I had learnt my dancing at the Hercules and Samson Ballroom, Norwich, right opposite its famous cathedral. Aaron worked for the governing party. He was a very intelligent man. He knew more of British history than I did. Also he was a likeable person. He and his wife took me to places of interest mentioned in our Bible. Also I lay in the Dead Sea, cannot say swam: impossible to swim. I left Jerusalem with heavy heart. So impressed by how the Jews had taken the desert and converted it to fertile land. Orchards of oranges and grapefruit everywhere. At the time I was there with the War on they were unable to export so you just helped yourself. Another thing I remember was the Jews building everywhere. Jews employing Arab labour. Jews and Arabs on the building sites joking, laughing with each other. I remember Aaron saying it is [only] the Arab leaders jealous of how we have changed the desert [...] Isaac and I returned to El Dabaa. Italy had declared war 10 June 1940. Not so many fun and games now. Our visits to the sea less. These beaches on the coast of North Africa were something to be remembered. Not sand: very, very fine particles where the sea over the centuries had broken the rock down.[...] [Runway sweeping: a dawn venture, to explode booby traps dropped by Italian aircraft over night] Usually four airmen walked in front. John drove [...] Knocker [624123 LAC Gordon “Knocker” Wade] exploded the offending missiles of which there were many. Fortunately there were no casualties during these dawn adventures. The Ities ceased dropping them after a month. We endured several bombing raids however. Each tent’s occupants dug their own slit trench air raid shelter. They were very effective about 6 feet deep and narrow. The only casualties were if you were in there first and some clown jumped in on top of you. The Ities were not that good. Invariably above 10,000 feet and shit-scared of our Gladiator fighter patrols. We always knew through message passed along the line when they were coming and our fighters would be waiting. I never did know how this worked. I suspected the Bedouins who roamed the desert respecting no frontiers and were paid by both sides. At El Dabaa we had a canteen hut. There was no NAAFI in North Africa but there was the good old Salvation Army, the Church Army and yes, in the towns, the Women’s Institute. On our camp was a hut run by a Church Army Captain, he too had served in 1st World War. Another lovable plump bald headed character. We had a table tennis table, dart boards, cards, chess, draughts, etc and a library of paperbacks. Amazingly, while in Blighty my Mum could not buy a tin of salmon, we could buy salmon sandwiches by the score, also eggs and bread. One evening we were playing table tennis in the Church Army canteen when the rocket went up. I do mean literally went up, for reasons I or my comrades never understood they used to fire a rocket as a warning of an impending air raid. To me it was like saying here we are come and hit us. [...] We rushed out and sought shelter. As usual they fell all around us. On the All Clear we sauntered back to our game. Entering the hut there was our Captain clearing up and wiping down the tables I said “Captain, one of these days they will hit this hut”. He replied “It will be God’s will, my son.” When I was a PoW I used to lay there and think of those times. It was God’s will there were such people as the Captain. He thought only of our comfort. No mention in despatches for such as them. My friend Isaac [Baruch] the Palestinian when we arrived in Greece got transferred to the Air Stores Park, several miles from us the other side of Athens, so I saw little of him for months. Then one of those strange quirks of fate. I was sitting at the roadside in Kalamata wondering would I be one of those lucky ones to get away. A lorry stopped near us full of airmen. Voice shouted “Abbie, here, here!” I ran to the lorry as it pulled away. It was Isaac. He shouted “Abbie, go to my home.” As previously mentioned I made it back to Egypt. At RAF camp Abu Sueir we were issued a complete new kit of clothing and posted to Lydda Airport, Palestine. Here again I draw attention to what happened to our Squadron in Greece as in Java. We got split up. Each group travelling by different methods and routes to reach a given destination. Luck played an important part I always felt. So in dribs and drabs we made Lydda Airport. Arriving there we were given all our back pay, as you can imagine by this time through our wanderings in Greece etc we were three weeks adrift. They gave us one month’s leave paid in advance. Previously unheard of, they paid us some subsistence pay. My mates went to Tel Aviv and stayed in a 1st Class hotel. What a life. We accepted it as a reward for what we had endured. As you can imagine I headed for Jerusalem. My welcome by the Baruch family was overshadowed by the fact that Isaac had not arrived. I told them of seeing him in Kalamata. Their anxiety was such I told a white lie and said I saw him boarding a ship. I also said as he was no longer with 211 he could well have gone to another clearing station who were not so efficient. Oh how I prayed. Thank God he turned up the next day. What a day too, a never to be forgotten party all their friends, relatives, neighbours. Their old gramophone played non-stop. Did they make a fuss of me! There I was, blonde hair, new colonial uniform, a sun-bronzed hero, friend of Isaac. Not my words, Isaac’s Father’s.[...] I celebrated my 21st birthday May 20 1941 with my mates on the Miramar Hotel Tel Aviv. Taking the words from that epic Great Expectations, “Such larks!” 211 then moved to The Sudan, at last a complete unit once again. Our mission: to train Aussie aircrews in combat experience. It was hot, it was humid, it was not good, but it had its moments. An open air cinema and a swimming pool. Most of all it was hundreds of miles from the War Zone. We called the Aussies BBCs: Big Booted Comedians. Letter 8—3—2001 (Greece) [...] Whilst at Menidi airfield (an ex KLM airport) we [Jim Fryatt and I] were in close proximity in as much as the photo section room was next to the armourers. Thus when things were quiet, not much on, we shared a mug of tea together. I remember one night in particular we celebrated someone’s birthday in the armament room. By the way, these rooms were on the side of the hangars. The night in question many of us got the worse for wear drinking ouzo and mavrodaphne, drinks we were not used to but so cheap to purchase. There is one photo that I took, its on French boat the Cap St Jacques sailing to Port Sudan from Port Tewfik. We had left Lydda airport, Palestine [ie on the Jun 1941 journey to form 72 OTU]. Rail to Port Tewfik then ship to Port Sudan en route to Wadi Gazouza. I played cards with Jim, “Swede” Revett (who came from Ipswich hence nickname) and Bill Pettitt, they were armourers. Bill Pettitt emigrated to South Africa. He died two years ago, heart attack. Revett I lost touch with as I did so many post war [...]

(L Abbs via JE Fryatt) [Len, later taken PoW in Java, wasn’t able to keep many of his photos, however, Jim (evacuated from Java aboard RAFA Tung Song) had a print in his collection. Len’s mates 545706 HJ Revett and 628869 WJ Pettitt were also taken captive in Java. All three survived. By one of the tricks of memory, this photograph of the June 1941 Red Sea voyage of Cap St Jacques from Port Tewfik to Port Sudan seems to have contributed to some confused recall by others, of the later 1942 Far East voyage from Port Tewfik (17 January), to Colombo (1 February) and on to Oosthaven (14 February 1942). The 211s sailed for the Far East from Egypt aboard HMT Yoma, not Cap St Jacques which was sailing between Bombay and Singapore at the time]. Greece. November 1940 Menidi Airport seventeen kilometres from Athens. We were given orders to make for the port of Argos where we would be evacuated by troopships. We travelled in convoy at first: it soon was apparent we were too big a target so split up. Gerry “shufti kite” (“shufti” Arabic: look see) would fly over to be followed by Stuka [Junkers Ju 87] dive bombers. The section I was in, three lorries, we saw the fighters coming in and ran for cover. They destroyed all the lorries. So legged it for Agrinion where we caught a train. We never made the town before nightfall so sheltered in olive grove where we met up with other RAF bods with the same idea. We were fortunate for they had cooked some Maconachies. Tins of soup with vegetables and meat. Absolutely beautiful at such times, having not eaten for 14 hours. We had our water bottles, carried tins of bully [corned beef], but that meal was one never to be forgotten. Little did we know what fate had in store for us and many came to experience worse, far far worse hunger. Next day we travelled in small groups and caught the train at Agrinion for Argos. The town was packed with British service personnel, some army such as those operating the ack-ack guns at the aerodrome, and had orders to leave. On train 15 minutes, we were attacked by dive bombers and fighters. The train stopped. I went to open the door to make a run for it. “Knocker” Wade, one of our little gang, gabbed hold of me, said “Stay, you stupid bastard”. He had a way with words. Sure enough many ran into the fields. Gerry returned and machine-gunned them, some fifty hit, 15 killed. When it quietened down we carried them into Agrinion. Some transport did come out, must have seen what happened. We carried on walking by night and sheltering by day which was safer as there were hundreds making for Argos. What transport there was you were unable to get petrol for. After eight days struggle, scrounging drink and food. The Greeks were kind to us but they too were not sure what tomorrow would bring. We could see Argos in the distance. What we saw was rising columns of smoke. Gerry had sunk the ships waiting for us. Walking along the road, there were six of us together, an elderly Greek came out and beckoned us into his bungalow. He made gestures indicating food and drink. In the bungalow there was Grandad, Grandmother, daughter, two granddaughters Rhola [Roula] and Christine, twelve and fourteen. Both granddaughters spoke quite good English. What a meal. Spaghetti, tomatoes and meat (goat’s or sheep’s) washed down by red wine. One can imagine how we enjoyed that after existing eight days on hard tack biscuits and bully beef. Oh, must not forget occasional orange, picked or should say pinched. We must have smelt for Mamma suggested we would like a bath. By the way, Mamma’s husband was in the Greek Army, serving on the Albanian border last they heard. A tin bath was produced. We filled the copper up from the well at the bottom of the garden. When the water boiled, [...] the tin bath was duly filled and tested for the right temperature. We tossed a coin to see who was to go first. Walter Gibson [Walter and Len were “best mates” as he explains later: they joined 211 Squadron on the same day, 12 March 1940]. We looked at each other. The family never left the room. I took Rhola [Roula] outside, she spoke the best English. I explained we would like some privacy. She went back in speaking in Greek. The family all burst out laughing but left us alone. We emptied and refilled the bath three times, toss of coin deciding who had the fresh water. While we were bathing, we ask the two girls to go into Argos and buy us some cigarettes. We had a whip-round and told them to buy some sweets and chocolates for their parents. They came back with the goods but said that German motor cycle troops were in town, mostly in the main square. As you can imagine, everyone started talking excitedly at once. Grandad signalled silence and through the girls, spoke to us. He had listened to radio and heard that the Australians were holding the line at Kalamata where British forces were being evacuated. He said “I will take you at nightfall to the pass through the mountain range that leads to Kalamata”. We left at 7 pm, we had torches and two lanterns. We walked and rested every half hour, though the olive groves mostly. It was nearly midnight when Grandad said “There is the pass ahead”. We had walked an estimated 15 miles. We shook hands, hugged each other and said goodbyes. I went back in 1994, another story, another time. We walked the rest of the night, best part of the next day and finally made Kalamata. We discovered there approx 500 airmen sheltering in a disused brewery. As you entered the brewery four airmen sat at a table and took your name rank, and number. A Sunderland aircraft [ie a Short S.25 flying boat of 230 Squadron] was coming in every hour, landing in the bay and taking fifty men off. Fifty names were called and you sheltered and waited at dockside. As one party went, another assembled and waited. Eventually they were taking 70, stripped to their underpants. It was hot in Egypt. We were there two days, our names were not called. We had two bad air raids with civilian casualties which never made our presence too popular. Second night we were resting on the cliff overlooking the sea. Moonlit night. It was so beautiful, so ridiculous. There was a crowd of us, one amongst us Flt Sgt Wrightson, wireless operator/air gunner. There was a light flashing out at sea. He jumped up and said “It’s the Navy, they’re coming in to take us off”. We ran down to the docks, sure enough hundreds of Aussies were there, mostly with war wounds. HMS Hero pulled along side the dock and dropped its gangplank. A voice from the bridge “Send them up in threes, fours, this is not a bloody naval display!” They took us out of the bay to a waiting troopship. Back and forward she went until there were 3,000 troops on the Delwarra [Dilwara]. We laid with our legs across one another. I was on the main deck. Come the dawn I looked around. There were seven merchant ships, 5 cruisers, 12 destroyers. It was not long before we were attacked. High flying and dive bombers. First attack they hit one merchant ship. Two cruisers, one each side, held her upright until they took 1500 men off. Some 500 were lost. Late that afternoon they hit another, same procedure, got most off. When the cruisers pulled away, the ships sank. Second day, dropped a bomb that blew a hole in our side and we listed over. The Captain over Tannoy announced he had shut that hold off to save ship. 250 in that hold. Our speed dropped to five knots, the convoy left us with one cruiser. We limped into Alexandria harbour [a] day later. All ships docked blasted their sirens. On the dockside, benches were set up and WVS women, [and] Salvation Army [...] served us with hot drinks, rolls, bowls of soup, cigarettes, sweets, you name it. Bath, change of clothing, pay, and a month’s leave. Compiler’s notes HMS Hero and MV Dilwara Roula Me 109s at Menidi MT convoys Letter 23—3—2001 (Java) [...] 211 were at Helwan Egypt being re-equipped. This was November 1941. They flew by hops to Palembang, Sumatra, the then Dutch East Indies. Besides the crews they took tradesmen, a skeleton staff sufficient to get them airborne on arrival. Assisted and working with Dutch Air Force, my information is they did go on one or two raids such as approaching Japanese landing craft. The aerodrome was defended by Indonesian coloured forces who put up no resistance when Jap paratroopers landed at dawn. Some 80 or so 211 personnel got away and made it to Java. The remaining ground staff who had not flown in the advance party to Palembang went by troopship. We had one naval cruiser escort. It always amazed me how around the world in the different theatres of war all hell is let loose and here are we lying sun bathing in the Indian Ocean listening to Vera Lynn singing “We will meet again some summer day”. We disembark at Oosthaven, Sumatra, 1600 hours Friday 13 February 1942. “Unlucky for some” [sic: 14 February, from Yoma’s Merchant Shipping Movement card and G/Cpt Nicholette’s 23 February report on Oosthaven]. We board a train, here we come mates, Palembang next stop. Not so, we travel for approx 3 hours and the train stops. Ordered to dismount we line up outside a small railway station. We are addressed by our Squadron Adjutant, Flt Lt Bright known affectionately as “Bright Eyes”. He wore spectacles. Ex-schoolmaster, loved and respected by every PoW who unfortunately were in the same camps as him [comrades in misfortune]. That's another story maybe later. To return to the railway station. Bright Eyes informs us that the Japanese forces have landed at the other end of the island. The train driver refuses to go any further. we march to a sugar plantation, where we spend a night in one of the warehouses. No grub available so we consume our emergency rations. Next morning we commandeer every available transport and with all possible speed make for Oosthaven, hoping the Yoma troopship is still there. The train had disappointed. We made it back to the ship and the Captain said he would wait until dusk for the stragglers. Weighing anchor he set sail for Batavia. Afraid of submarine detection he sailed close to the land in shallow water. So shallow for the first time in my life I learnt the true meaning of swinging the lead. We made it mid-morning next day. Bright Eyes informed us we were to march to a Dutch Army barracks on the other side of the town where we were to be billetted. We had left the town when one of the worst air raids had ever seen commenced. Estimated 300 bombers in waves of 27 in each formation attacked the harbour. One formation broke away, coming in low, machine gunned the road we were on. On each side of the road were 6 foot deep monsoon drains which everyone dived into. Fortunately the only casualties were those of the men who landed badly when they jumped. In the harbour was the cruiser Exeter, six destroyers, one of which was the Jupiter, and three Dutch naval vessels. As you can imagine, they were firing everything they could at the raiders. We learnt later no naval vessels hit, some merchant ships set on fire. One or two warehouses destroyed and one Gasometer [...] one of those huge gas tanks one used to see in every city. There were 300 civilian casualties. We had two weeks at the barracks and it was like a summer holiday. Looking back it is hard to believe it happened. We were actually paid by the Dutch military command and a guilder a day colonial pay extra. Guilders in those days about two shillings. It would buy 20 cigarettes and two pints of beer. We reported to Dutch air force base each day at 8 am. It was a supply base, no planes only equipment. They didn't know what to do with us. They had sufficient staff anyway so eventually they sent us packing. Swimming pool all day, cinema or cabaret at night. Invasion imminent, there we were living like tourists. I made friends with an Eurasian girl who took me to meet her parents. Should say Mum, sister and brother. Father was in the Dutch army, far as they knew in Surabaya. If we airforce had a command unit it was non-existent, we did as we wished. Then the Japs did land. There was a huge sea battle in the sea off Java. The six British destroyers actually sailed between the landing barges picking them off. The heavy battleships of the Japanese from a distance of 15 miles picked the destroyers off one by one, ignoring the fact that they too were hitting their own troops. Apparently they estimated they could lose a third of invasion forces and still take Java. Which as history knows, they did. Day after battle, steamship Orcades was berthed in Batavia. We boarded her bound for Australia. We thought we would get away from Java. “He who fights and runs away lives to fight another day” [...]. These words were spoken by Walter Gibson, my best mate, as we leaned over the rail watching others boarding. There must have been about 150 of 211 Squadron on board the Orcades. “Bright eyes”, bless his cotton socks approaches our little gathering, Walter Gibson, John Stevens, Ginger Worrel, Joe Smart, Knocker Wade, yours truly, others whose names I can't recall. This is what “Bright Eyes” said. “There is a Yank auxiliary unit holding the approach bridge. The Captain asks for 100 men to leave the ship to let Dutch women and children board”. Every 211 man followed “Bright Eyes” off that ship. “What now Sir?” [Bright consulted with someone, Len does not recall who] He came back with orders for us to go to Jamis in the hills where all British Forces would make a stand. Ye Gods! Brave words indeed. We marched to the railway station. The station master was vague about time of arrival next train, not surprising really. Whilst waiting we heard noise of approaching aircraft so sought cover. They passed overhead but bombed the dock area. Whilst waiting at the station a Dutch Army convoy stopped to replenish their water supply. We ask their destination and would it be near Jamis. He said [it] would and gave us permission to travel with the convoy. “Bright Eyes” our Adjutant didn't mind as long as we made it there. Our group of mates who had been together on the Desert, Greece, Palestine and Sudan hopped aboard where there was space. It was an infantry company we joined. They were post haste to join the main Dutch forces engaging the Japs. They had been guarding an area of the coastline where they might have landed. 2 hours on the road they stopped and we enjoyed fried rice and fish washed down with coffee. Not what we were used to but boy was it welcome, we relied on handouts. On the road again 1/2 an hour or so later we stopped and we were being fired on by machine guns. A Dutch Sergeant in our wagon said “Get under the lorry, lay behind the wheels”. They were paratroops who had blocked the road. They were up in the trees. Whilst jumping for cover one Dutch lad got a bullet in his shoulder. We had rifles and ammunition. Laying behind the rear wheel I started firing into the trees. Knocker Wade was beside me, his rifle pointing out other side of wheel. He said “Stop firing you stupid sod. Only fire when you see the flash from their guns. Then you know you have a target”. Knocker was a regular defence gunner. What I mean is where-ever 211 had an airfield we had sandbag machine gun posts. Also in convoys we mounted machine guns and Knocker was always there. Good advice. I did however remind him I had done an Air Gunners course. His retort: “Shut up. Stop panicking and don't waste bloody ammunition”. We were all a bit tense as you would imagine. The Dutch soldiers lobbed a few grenades into the area where the enemy fire was coming from. Sprayed the area with intensive fire. God, I thought, I am glad I joined the Air Force. It was quiet for about an hour when the Dutch medics came around seeing to the wounded. Fortunately none killed but some bad wounded. The Dutch officer walked around speaking to everyone. To us he said “Are you glad you joined our convoy now? Anyway well done, in another 30 miles you can join your comrades. My wireless operator has been in touch with headquarters and our information is the British are assembled at Jamis.” Sure enough they dropped us off, we shook hands all round and they pointed us in the right direction. We must have climbed upwards and upwards walking for a mile or so when we found the camp. There must have been hundreds of airmen assembled but not one we recognised. We had what was considered at that time a good meal. Bowl of soup, 1/2 loaf of bread and mug of tea. It was nectar. The next morning we received the news that the Dutch had capitulated. You can imagine the situation. Everyone was looking for advice. Wing Commander Gregson: “We will fight. The British will make a stand here”. I remember Knocker saying “I sure will Abbie I've 40 rounds left, wonder what he has got”. We had a chin wag, that is Walter Gibson, Knocker Wade, Bob Kerswell and self. For our sins we decided to pinch a truck, make for the coast and persuade a fisherman to take us to an off-shore island. Wasn't there plenty of those off Java, no problem. This we did after doing a reconnaissance of the vehicles about, we picked a 30 cwt truck with nearly a full tank. Bob drove, Knocker in front, Gibby and I in back on a tarpaulin. As we were pulling away we were approached by a Flying Officer who signalled us to stop. Bob drove on and as we passed him he shouted “I'll have you court-martialled”. Gibby said “I think he means that Abbie”. We passed thousands of Dutch troops (Indonesians) carrying white flags some with Japanese flag. Eventually we made Tjilatjap. There were some airmen sitting on the side of the road. Bob stopped and asked “What's the gen, fellows?”. They said “What's your unit?”. We said 211. They said “There's loads of your fellows on the 'drome”. Following instructions we found the 'drome and bless his cotton socks, Flt Lt Bright (“Bright Eyes”). Also Sqdn Leader Padre Rourke [Rev PT Rorke RAFVR] who was to be remembered as one of the finest, bravest men who ever lived. Padre Rourke took his uniform off and changed for an airman's, for he seemed pretty wised up, they did separate senior officers from other ranks. The Padre said his place was amongst the men and indeed he slept in our billets. I saw him, when a prisoner, take a rifle off a Japanese guard who was beating hell out of an English prisoner. The Padre took the rifle, stood to attention, bowed to the guard and handed him the rifle back. The guard stood flabbergasted. Raised his rifle to hit the Padre, stopped. Then said “Muchigo” (come with me). He took the padre to the guardhouse. This was at Yar Mari camp, Surabaya where there were at least 3,000 prisoners mostly Dutch. Rumours spread round the camp like wildfire. They will shoot him, they will beat him up. About 3 hours later Padre returned to his hut with packet of Japanese fags and a bag of fruit. The interpreter said the camp commandant, a Major in the Emperor of Nippon's Imperial Forces was a true Bushido and admired the courage of the Padre. From that day some of the guards even saluted him. At Malang camp when we were made to witness the execution of four prisoners I said to Padre Rourke “Where is your God now? He let that happen”. He replied “What you witnessed this day was not God's work but man's”. [At the aerodrome at Tjilatjap] We met several of our old comrades so decided to await our fate with them. Bright Eyes told me to destroy photographs that I had, about 150. Also Log book. The first few days we saw few Jap soldiers and did pretty much as we liked. For our own safety we were advised to stay on the camp at night. I made friends with a Dutch girl Pam de Bly and met her family. When we were eventually moved from the drome I left her with souvenirs that I had accumulated on my travels. Also medals and a cup I had won in boxing and swimming whilst in the Forces. She promised to send them to my parents address. I never heard no more. Who knows what fate awaited them, for eventually the white Dutch women too were interned. Lt Colonel Soni, a Japanese camp commandant once said if the women had fought for Java they would never have lost it. Soni lived in England at one time, spoke perfect English. He was one of the better ones. If my memory serves me correctly, a company of Japs turned up one morning at the 'drome and things changed dramatically. 750 of us were put on a train and taken to Malang. We travelled all day and the Japs treated us well. When the train pulled in at a station they let us buy refreshments. Most of us had money. One Jap sergeant told us to hide it as when we got to Malang the Kempe-Tai (Gestapo) [Secret police] would take it from us. Our escort to Malang were the Jap Imperial Guards, they actually fought taking Java. They treated us with respect and some of them played cards with us on the train. Many times I thought of them and that they can't all be as bad as this bastard who is kicking me as I lay on the ground. We arrived at Malang. Things did change. For the worse. [Postscript] I then went to Sumatra worked on building a railway. They only speak of the Thai railway. In Sumatra, they built a railway from end to end. Pakenbaroe to Palembang. Workers started from both ends and met in the middle. At one time, building a bridge over the Inderhari we were 60 feet above the water. 650 men lost their lives building that bridge. I was working with an Aussie who came from Tasmania. I only remember him as Blue. Going to work one morning he said “Abbie if that bastard sticks his bayonet in my arse today I'm jumping”. He did and took the Jap with him. I last saw him when they surfaced, he still had hold of the Jap. The current was fast, both were never seen again. All survivors of Haroku worked on that railway. Of the original 2,000 that went to Haroku at the end of the war 80 survived. I had malaria 28 times on Sumatra. You worked in gangs of ten, if seven were sick [the gang] got rations for three. No work, no food. We were counted out of the gate to calculate next day’s rations. Sometimes fit men helped the not so fit to work to boost the rations. I never made it to the link up [the meeting of the railway lines]. Went back to base camp with dysentery and malaria. Normally they would not have bothered but it was June 1945 and for them the writing was on the wall. August 19 1945: a Major, two staff sergeants and 100 paratroopers dropped in on our camp. The next [day] planes dropped food supplies and medicine. [...] Suffice to say I was one of the Fortunates. I spent 26 weeks in RAF Hospital when I returned home. I was discharged on medical grounds. It broke my heart for I loved the RAF life and had intended to sign on. I have had a wonderful life thanks to my Betty and family. Squadron Leader The Reverend PT Rorke 60059 RAFVR Through all that Abbie and others like Foster Catterall have reported of his compassion and bravery in ministering to fellow FEPoWs, Pat Rorke survived in the face of the most brutal treatment by their captors, the Imperial Japanese Army. He was among those Mentioned in despatches “for gallant and distinguished service whilst a prisoner of war in Japanese hands” (London Gazette 1 October 1946). After the war, Padre Rorke returned to parish duties in the United Kingdom, to retreats, and to various writings about the spirit. His little book of collected writings, Greatness of Heart, saw several editions between 1979 and 1988. In it, Pat Rorke called much upon the travails he and his RAF comrades had endured, incorporating his earlier booklet The Wisdom of Adversity as well as other thoughts arising from that long captivity. Father Patrick T Rorke SJ died at the age of 86 in September 1990, well-liked, much respected and never forgotten by surviving FEPoWs. Photos from Len

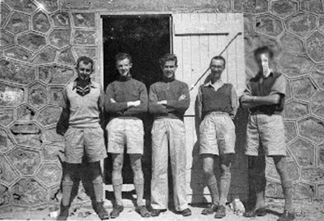

Len recalled the men as Schimical (Palestinian), Shaw, Abbs, Ryder, unknown, Walter Gibson, Simpson (seated, right) and Baldwin (standing, right). The Photo Section in December 1941 still included 615342 LAC Abbs LW, 552256 LAC Baldwin RJ, and 552272 Cpl Gibson W. Of these, Len and Walter Gibson were the only ones who went to the Far East and into captivity.

Their companion is a Greek sailor. A cup of char, a fag, and that look. Gibbie wears his tin hat and a wry grin but they all have the look of men who have seen much, expect more of the same—and are ready to keep going.

Both these photos travelled a long, hard journey. They bear the stamps of the Imperial Japanese Army, having been kept safe despite captivity. Alan Conrad also numbered Fletch and Con Conder among his mates.

Taken at El Daba, 12 March 1940.

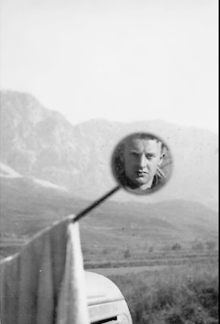

Abbie’s best mate “on the Squadron”: a cracking shot from Greece. Walter “Gibbie” Gibson died of dysentery in Fukuoka, Japan in January 1944 aged 23 years. In 1947, Len and Betty spent their honeymoon in the cottage where Walter had been born. Gathering sunset From time to time in those days, Len had expressed typically modest but pleased surprise that anyone would have bothered to write about the efforts of the Squadron’s ground trades. The plain fact is that, working under difficult war-time conditions far from home, young men like Len played a very big part in keeping the Squadron operational. No mean achievement. Not only that: he was one among 346 of the Squadron known to have been taken prisoner on Java in 1942 and one of only 166 of that group known to have survived the next three years of captivity. However painful the memories, he returned home and made a long and fruitful family life with Betty. As the years passed and their five daughters flourished, Len came to refer good humouredly to his home-life as “petticoat government”, with Betty cast as OC and Maz as second in command. Over recent years, Betty’s health declined and the role of carer fell increasingly to Len at home in Lowestoft. It is a sadness to report that Betty Abbs departed this life on Friday January 14th 2011, at James Paget University Hospital in Gorleston, Great Yarmouth, after a long illness. After Betty's death, Len continued to bat on alone in their little house. Gradually, his letters became less frequent, although initially he adopted an ingenious work-around with his own sensible request, to one or the other, to share his letters. As is often the way as the sunset shadows lengthen, the intervals became long indeed: family and home first, of course. In August 2013 I was able to make contact with Len and Betty’s daughter, Marion (Maz) Abbs. Her kindly response to my enquiry was that over Christmas 2012, Len had been given a two-week rest in residential care. During that time it became apparent that the dear old lad, battling with dementia, was no longer able to return home. Len turned 93 in May 2013 and, although his memory was failing him, he continued well enough and safe in care, though missing Betty greatly. During family visits, he would enjoy looking through his old photo albums, which would prompt him to retell some of the yarns about his war-time adventures over 70 years before. And if, as such things go, they sometimes turned out to be rather different to the old stories so oft retold, no matter: as Maz remarked, “It is good to see him laugh.”

Farewell, old friend In times to come, when the family gather for the big occasions, Len and his Betty will be remembered fondly and with much laughter, with his yarns and his sayings at the fore: "Keep 'er goin' Bor!", the Singing Postman, listening to Mario Lanza while making furniture in his shed, his “petticoat government” and all the rest. Dear old Abbie. What a nice chap. Farewell, old friend. Sources Java FEPoW 1942 Club Prisoners in Java Hamwic 2007

www.211squadron.org © D Clark & others 1998—2025 |

||||||||||||